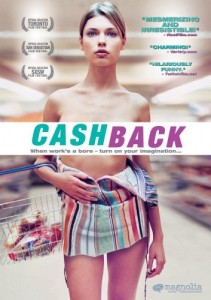

Cashback

Netflix hates meNetflix has been pushing me to watch Cashback(2006, Sean Ellis) for a long time now, and so on a rainy Monday spent procrastinating, I brought it up. After watching the film, I’m a little hurt that the Netflix algorithm thinks so poorly of me. Never have I seen a film this misogynistic, this objectifying, this disturbing. The film promotes the nerd “nice guy” narrative, features plenty of soft-core nudity, and portrays sexual assault as romantic. All this is done while trying to convince us that the protagonist is still a great guy. As far as adolescent wish-fulfillment fantasies go, it doesn’t get much better than this.

Ben is your classic Mary Sue character, a stand-in for the director* and every lonely straight middle class white male. Every guy around him is a jerk or a loser, and bullies him for no reason. The girls, of course, love his shy, sensitive demeanor, even if they go out with the jerks. He’s presented as a misunderstood genius, but the audience is given no evidence for it. All he can utter is trite wisdom that would be better found on twitter. Highlights include phrases like “You just have to see that it’s wrapped in beauty and hidden away in between the seconds of your life. If you don’t stop for a minute, you might miss it”. While a “nice guy” might find this inspiring, no thinking adult would. Most egregiously, he’s gifted magic powers, just to emphasize his specialness.

While a tortured artist, Ben’s uses his status as an artist to elevate himself above others. He talks about his beauty and wonder at the female form, but does not care to paint anything else. I don’t think he He does, however hold an extremely high opinion of artists, and in extension, himself. Ben says during the film:

- “I read once about a woman whose secret fantasy was to have an affair with an artist. She thought he would really see her. He would see every curve, every line, every indentation and love them because they were part of the beauty that made her unique.” *

However, Ben never shows any insight or talent as an artist. His “gallery” is laughable; All of his paintings are of the romantic leads in various states of undress. The only evidence that artists are special romantically is that Ben is only person who is not a complete jerk to women. If he showed any sort of artistic depth it would break the viewer’s fantasy that like Ben, they are the only ones who appreciate women. The film indulges our “sensitive artist” through hordes of naked women, all presented in a sexualized poses, which has no purpose other than to satiate the lusts of the audience. The only purpose this serves is to reassure the nice guy that they can view naked women without feeling guilty about objectification. After all, it’s not pornography, it’s art! * And while female nudity is always beautiful, the same can’t be said for men. The only male nudity we see is an old man modeling for Ben’s art class, who farts while the students draw him. The film disguises Ben’s - and in extension, the nice guy’s insecurity about his own sexuality as an artist’s appreciation for the female form. In *Cashback, all male sexuality, except for Ben’s is aggressive, crass and gross. Ben’s coworkers tell raunchy jokes, treat women as sex objects, and expect women to screw them at their whim. Ben says he is different, that he is “nicer” than the men around him, because he thinks of relationships, not sex. After all, he is the only guy who does not line up to watch Natalie pull her skirt up, is nice to the girl with the broken arm, and comforts Sharon when she has a bad date with a co worker. But Ben is far worse than the “jerks” he is supposedly above. He never asks the female patrons of Sainsbury if he can draw them naked. This is a sexual assault fantasy, no matter what kind of pretty terms you couch it in. In contrast, the jerks mostly seem to respect consent - Ben’s boss asks Sharon if she wants to have sex with him and grudgingly accepts her refusal. Natalie the stripper enforces her own consent and the men accept her rules. In contrast, Ben uses deception or magic powers to get what he wants. One has to wonder if his niceness is just another strategy he employs to get women. Despite Ben’s platitudes, he respects women the least out of any character in the film. The only reason he seems ok is that he is so cowardly he only acts out his rape fantasies when he can stop time.

Cashback shows very little respect for men, either. While he would never admit it, Ben’s entire life revolves around women. If he’s not working, he’s staring into space, painting women, or thinking about his relationships. When he talks to his friend, he talks only about women. Every event he narrates to us is about past relationships. Ben isn’t a talented artist - it’s just a persona he adopts to get women. The other men in Cashback are just like Ben; their “hobbies” serve only as personas, means to getting laid. The only male in the film that has any sort of interest outside of relationships is obsessed with kung-fu and shows no interest in sexual relationships or friends at all. In the world of Cashback, if you are male, you are either obsessed with sex or completely celibate - there is no middle ground.

As poor a character as Ben is, his love interest is worse. Sharon is a one-dimensional woman that could only exist on a pedestal. She’s completely unintimidating, and seems to have no life outside of Sainsbury. She plays into the nice guy fantasy of the male role as protector against the jerks. She is exactly like Ben - talking to Sharon is like talking to a sentient mirror. Sharon is a woman constructed to fit into Ben’s life. She is easily swayed by romantic gestures. Even when she is mad at Ben, she immediately forgives him when she sees his gallery. She’s not creeped out at all by the fact that Ben has made hundreds of drawings of her, where any sane person would.

This is the worst flaw of Cashback - Sharon’s only purpose in the film is to complete the life of Ben. The nice guy believes his life is incomplete without a woman, that a relationship is the cure to depression. His personality becomes defined by his niceness, to the point where relationships are the only facet of his life. No wonder it’s such an unattractive personality - the nice guy lacks any unique features of his own other than constant self-pity. In the relationships idealized by the nice guy the woman is put into a role as therapist and lover to the same person. There’s no room for her to define her own personality - it’s already been forced on her. The only times Sharon is allowed weakness is when Ben is trying to score points by comforting he. Ben is so narcissistic he sees his romantic gestures as gifts in of itself. This is most evident when Ben gifts Sharon his ability to stop time. Ben even adopts her dream to travel South America into his own when he incorporates it as a career trip. There is no room for female autonomy in Cashback, it’s far more important for women to heal lonely nice guys than to strike her own path in the world.

Ben’s ex-girlfriend, in contrast, is a bitch, constructed only to be undeserving of Ben’s attention. When she breaks up with him, she screams at him and throws a lamp at him. Why does she do that? We are never given a reason, and it’s hard to imagine someone as passive as Ben actually provoking anyone’s anger. And when Ben actually gets together with Sharon, she wants Ben back. Everything about her is designed to make the audience hate her, a revenge fantasy for every nice guy who’s felt the sting of rejection. The most empowered character is Natalie the stripper. She has found empowerment by rejecting relationships and selling her body. Unlike Sharon, she gets to set boundaries with men - nobody can touch her without her permission. Unlike Sharon, she can be dismissive of men. And for what it’s worth, she seems happier than anyone else in the film. But for all her empowerment she is still trapped in the warped perspective of the nice guy. Natalie allows the nice guy to fulfill his need to consume sex while keeping that need separate from his romantic interest, a way to escape his guilt. Natalie becomes a sex object, who a man will consume but never love. The implication that sex workers do not need to be loved, like anyone else is disturbing. Is Natalie not human as well? In Cashback a woman can occupy only three roles - girlfriend, bitch or whore. No wonder Natalie works as a stripper - it’s better than being put on a pedestal.

The problem with Cashback is not that it presents a fantasy - it’s that it presents a sick fantasy. If you believe in the narrative the film espouses, you need help. There are jerks in reality, but most men are not jerks. The women who reject you are not bitches. Most people find partners, and yes, they have flaws and sometimes are mean. And yes, some people are abusive. But most live normal, happy lives. Are they jerks for having a happier life than the nice guy? The nice guy needs to examine his own life, and why he is unhappy. He needs to drop the simple categories and accept people for all their complexities, their virtues and their faults. He needs to see that there is more to romantic relationships than grand romantic gestures. It’s about sharing yourself, building a connection - and the problem with the nice guy is that he has nothing to share. He needs a life outside of the relationship - and so does his partner. He needs to embrace healthy expressions of his sexuality rather than view it as inherently predatory. Sex is a wonderful part of the human experience, and there’s no need to feel guilty about our lust. Of course, Ben’s time-stopping fantasies are inherently predatorial - no wonder he feels guilty. And Sean Ellis should be ashamed of peddling rape apologia.

While Cashback’s perspective is deplorable, the incoherent plot makes the film essentially unwatchable. Ben has the power to stop time, but it’s completely irrelevant to the story. It becomes an excuse for the director to try and drop his Ben does not use his powers to enrich himself or help people

- his only use of his power is to remove the clothes of female patrons of Sainsbury. When the director introduces the idea that there are others who share Ben’s powers, it’s promptly dropped and never mentioned again. Events share no relationship with each other; it’s like watching a series of 10 minute episodes that attempt to enforce patriarchal norms. The film is little more than exploitation, an excuse to watch pornography without the guilt.

If only the film had some self-awareness about the absurdity of Ben’s beliefs, this film could have been a wonderful look at how narrative shapes our beliefs about relationships. But instead, the film does nothing but validate Ben’s viewpoint. All the jerks get their comeuppance. Ben realizes his dreams through no effort of his own. Ben gets the girl, and his ex-girlfriend begs for him to come back. One gets the feeling that Ben is living out the director’s teenage fantasies.

*In an earlier draft, I actually thought the protagonist’s name was Sean.

<< Previous Next >>