Notes on Early Chicago

Before

400 million years ago, before the brutal winters, Chicago was once a land of perpetual summer. Warm, shallow seas covered the entire Mississippi Valley. Where skyscrapers now rise, coral reefs once bloomed. These reefs would turn into limestone, providing a solid foundation for those skyscrapers. Over the last million years, ice sheets swept down the valley and receded, draining Lake Michigan a little in the process each time. Glacial rivers a mile wide rushed down the valley, but they too shrank. Left behind were only the Des Plaines River, draining into the Mississippi, and the Chicago, headed towards Lake Michigan. Connecting the two rivers was a swamp known as Mud Lake.

And the reason for Chicago.

In the 1600s, fleeing Iroquois raiding parties, small bands of Potawatomi moved along the coast of Lake Michigan. There, on the southern shore of the great lake, they found turkey, deer, and buffalo drinking from the waters. Better hunting than anyone had ever remembered. Their cousins, the Illini and Miami, had moved west and south, respectively, after a series of wars; the land was empty. The Potawatomi spread along the shores of Misch-i-gon-ong, or Place of Great Lake, trading their nomadic life for a settled one. Visiting friendly neighboring tribes was easy because a series of hunting trails converged on the little river Checagou, named after the wild onion that grew on its banks. In time, the Potawatomi prospered and felt secure enough to welcome the first white settlers to their lands.

In the spring of 1673, French explorers left Mackinac seeking converts, furs, and a waterway between the Gulf of Mexico and the Great Lakes. Heading south to Arkansas, friendly Native Americans advised them that going farther would be exceedingly dangerous. But on their way back, they were advised to head back to Michigan using the route they used: porting their canoes between the Des Plaines and the Checagou via Mud Lake. There, the French met the Potawatomi, who were welcoming and eager to trade with the new arrivals. Delighted by his find of hunters to buy furs from and a link between Lake Michigan and the Missisippi River, French explorer Louis Joilet noted that the mouth of the Checagou made an excellent harbor and that it would only be necessary to build a canal over Mud Lake to join the two waterways. Prophetic words. But it would take another 175 years to build.

For a time, trade thrived at the mouth of the Checagou. That all came to an end at the turn of the century. The Fox tribe, angry that the French had given arms to their rivals, the Sioux, banned the white man from the portage. For 70 years, it would remain closed, with little known about life on the western shore of Lake Michigan. That is, until Jean Baptiste Point du Sable, Chicago’s first settler, established a new trading post in 1772 and married a Potawatomi woman. The Native Americans tolerated du Sable because he was not white but a black man from Haiti. Convinced of Chicago’s commercial potential, he moved his family there in 1775, and the first recorded Chicago birth was his daughter Suzanne. The trading post thrived even as the French lost control of the area and ceded it to the British, who in turn lost it to the newly formed United States.

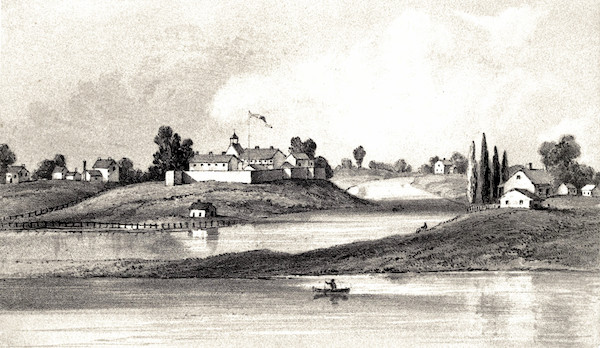

With the Treaty of Paris in 1783, settlers poured over the Appalachian mountains to settle the newly claimed land. The new settlers quickly clashed with the Native Americans, armed by the British. A war broke out, and the natives were eventually defeated at the Battle of Fallen Timbers in Ohio. As part of the peace treaty, General “Mad” Anthony Wayne demanded land at the mouth of the Chicago River. It was the first indication the American government saw the strategic importance of Chicago. Eight years later, the United States Army established Fort Dearborn at the mouth of the Chicago. The government intended to break the British-Native trade, and agents were ordered to undersell the British at any cost. Traders and settlers moved in, but the little town did not grow quickly, probably because of the harsh weather and marshy soil.

Soon, hostilities broke out between the increasingly pro-British Potawatomi and the Americans. As the War of 1812 approached, the younger generation of Potawatomi leaders vowed to destroy the fort. Outgunned and outnumbered, the fort was given evacuation orders. Captain Nathan Heald distributed the fort’s supplies to friendly natives, except the ammunition and liquor, which he had destroyed. He would regret that decision. Enraged by the destroyed supplies, the Potawatomi attacked the retreating soldiers and civilians and destroyed the fort.

While the first attempt at settling Chicago by the United States ended in disaster, the government was determined to settle the west, and the Chicago area was a priority. Though the fledgling government was bankrupt from the war, they acquired 2000 square miles around the mouth of the Chicago River from the Native Americans and authorized the Illinois government to build a canal. However, the year-old state government didn’t have the $700,000 required to dig the canal, and the project was dropped. The federal government eventually set aside some money to build a harbor and built a pier 1,000 feet into the lake. Supervising engineer Jefferson Davis did not realize that said pier would wreak havoc with the southern shoreline and the price Chicago would pay to save it.

The federal government, eager for cash, fell back on a familiar strategy: buy the lands from the Native Americans for a pittance, force them to reservations west of the Mississippi, and resell the land to homesteaders at inflated prices. In order to attract settlers and fund the canal, the state of Illinois was granted half of the 2,000 square miles acquired earlier, including all of the land along the Chicago river. As for the Potawatomi, they settled in Kansas, a poor people. But the lands they left behind would become one of the wealthiest metropolises the world had seen.

Boom Town

With a new harbor and the natives removed, Illinois and the federal government went about selling their newly acquired land. However, there was little demand for it until 1835, when the Illinois Legislature finally got backing for a canal from eastern bankers. Speculators who had bought lots a few months ago resold them for three to four times what they paid. As word spread that Chicago would make you wealthy, hustlers poured in to buy land. In two short years, Chicago had grown from a muddy village of 200 to 3,260. In two more years, it would incorporate as the City of Chicago rather than the Town of Chicago.

The canal broke ground on July 4th, 1836. After many long speeches and a fight with children who had put mud in the official wheelbarrow, Chicago dignitaries shoveled the first dirt of what would become the Illinois and Michigan Canal. Of course, building the canal was easier said than done. The original $700,000 estimate ballooned into $8 million, and the first 20 of 28 miles turned out to be limestone rather than soft clay. By the time the canal was finished in 1848, city leaders were saying that what the city really needed was a railroad. But with the opening of the canal, Chicago boomed again, growing from 20,000 to 30,000 in two years.

The city was not a pleasant place to live. Nobody had thought to drain the soil or pave the muddy streets. Swedish immigrant Gustaf Unionius wrote:

The surroundings harmonize with the general character of the city - with a few exceptions, resembling a trash can … The entire area might be likened to a vast mud puddle. I saw, again and again, elegantly dressed women standing on street corners waiting for some dray in which they might ride across the street.

Human and animal waste flowed into the Chicago River and drained into Lake Michigan. A water pipe extending only 150 feet into the lake sucked that waste back into the city’s water supply. Cholera and typhoid plagued the city, killing 5% of the population in an 1854 epidemic.

Beyond smelling foul and creating a health hazard, the harbor built by Jefferson Davis began to reshape the geography of Chicago. The north side of the pier collected sand, creating natural landfill, but the south side of the pier began to erode. After each storm, Michigan Avenue flooded. The wealthy who had built mansions facing Lake Park demanded their property be protected, and Chicago leaders asked the federal government for funds to construct a breakwater. Washington refused, forcing the perpetually broke city and legislature to find another solution to save Michigan Avenue. They found a savior in the Illinois Central Railroad, which volunteered to construct the breakwater. All they wanted was the shoreline.

The Illinois Central had powerful backers, including Senator Stephen Douglas and Representative John Wentworth. They preferred a terminal in the western, industrial part of the city, but had acquired land near the lake, and would settle for it. Mayor Walter Gurnee was in a bind. If he allowed the railroad to be built, his neighbors would be at his throat for putting train tracks in their front yard. If he didn’t, their houses would float away. Matters came to a head at a City Council meeting on December 29, 1851, where an ordinance passed to grant the land to the Illinois Central. Gurnee vetoed the ordinance. However, North and West Side constituents pressured their aldermen to overturn the veto. After all, the city would eventually have to construct a breakwater. They would prefer the cost to come out of the pockets of the Illinois Central than their own taxes.

In June, Gurnee’s veto was overturned. The result was a compromise that everyone would come to hate. The Illinois Central lost all hope of a terminal where it wanted, would be prohibited in court from expanding, and eventually forced to spend a fortune covering its tracks. The city, when it was finally able to fill in the lake and build a lakefront park, was stymied by the railroad tracks. And when the tracks were covered, another fight would erupt over who owned the air rights. But in 1852, nobody complained.

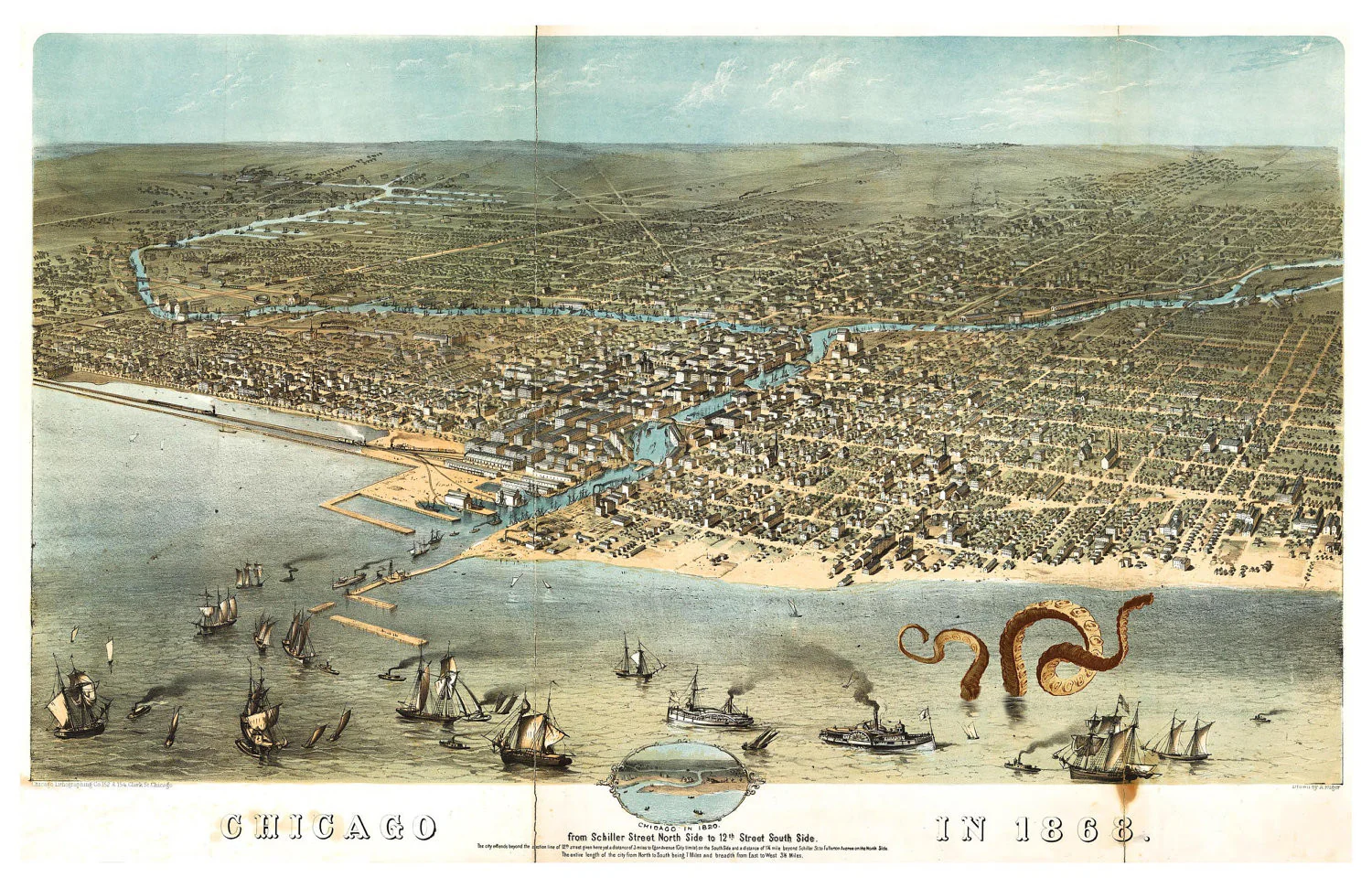

Chicago would soon become the railroad capital of the world. In 1850, only one line entered Chicago. In 1856, Chicago would host 10 trunk lines with a combined 3,000 miles of track. 58 passenger trains and 38 freight trains entered and departed the city daily. The population of the city tripled, from 38,700 in 1852 to 120,000 in 1857. Along the new railroad tracks, industry sprang up: warehouses, factories, and packinghouses. It was not an orderly planned city, and city leaders would spend decades attempting to consolidate the railroads.

But what the railroads created in disorder, they made up for in wealth. Enough wealth for the city to attack its chief problem, sewage. A new intake pipe two miles into the lake was constructed, and the Illinois and Michigan Canal was dredged deep enough to reverse the flow of the Chicago River into the Illinois River rather than the lake. The world’s second underground sewage system started construction in 1856. Brick sewers were laid, then covered by raising the streets. The first floors of houses became semi-basements, a Chicago architecture tradition that continues to this day. Other houses were moved by sled to another part of the city, with the occupants inside going about their business. One tavern was even moved with patrons drinking inside.

The Illinois Central, hungry for more lakefront land, bribed the legislature in 1869 to give them full control of Chicago’s harbor. As part of the deal, the railroad would pay the state $800,000 for the land, to be used as a park fund for Chicago. Governor John M. Palmer vetoed the bill, complaining that the land was worth $2.6 million and Chicago could permanently lose its harbor. The legislature overrode his veto but repealed the law four years later in the face of public opposition. However, the Illinois Central insisted the act was a contract and irrevocable. It continued to fill in the lake until the Supreme Court ruled that Illinois had a right to repeal the sale in Illinois Central Railroad Co. v. Illinois. The city would spend the next hundred years struggling to reclaim that lakeshore.