The Culture Map: How to Navigate Foreign Cultures in Business

Have you ever found yourself working on a multicultural team and unsure how to interact with them? Then the book The Culture Map by Erin Meyer is for you. The author is a business professor that advises clients on how to work with multicultural teams. She divides cultures into 8 traits that fall onto a spectrum, and gives advice on how to work with cultures different than your own. For example, some cultures have different attitudes about time. Some cultures consider you late if you don’t show up at the exact time of an appointment (Germany), while some might give you a leeway of 10 minutes (France) and some might be an hour late (India). So on a spectrum, you might see it like this:

Strict <—- Germany — France ——- India —> Flexible

This is important in evaluating how you will interact with another culture, because other cultures are positioned relative to your own. The Indian will find both the French and German extraordinarily inflexible on appointments, while the German will think the French are perpetually late and the Indian worse. The Frenchman will be somewhere in between.

Chapter 1: High vs. Low Context

In the US, we communicate very explicitly. Take the classic business presentation advice: Tell them what you’re going to say, say it, then tell them what you just said. This is an example of a Low-Context culture: We assume very little shared context, explicitly spell out our ideas and often repeat things. The speaker is more responsible for accurately conveying information. High-Context cultures, on the other hand, convey a lot of information implicitly. For example, in Hindi, the word kal means tomorrow and yesterday - you have to deduce the meaning of the word from the sentence. In high-context cultures, the listener is more responsible for receiving and interpreting the message.

Another example the author gives is when she went to India, and asked the concierge at the hotel about a good restaurant. He recommends a restaurant, and tells her to take a left from the hotel. However, after taking a left at the hotel she is unable to find it. After two attempts, the concierge takes her there, and she finds out that it’s a 10 minute walk from the hotel. A native Indian would have known to keep walking, but she didn’t.

The worst confusion, however, comes when two different high context cultures interact. This is because they are both expecting messages to be transmitted in subtext, but both cultures have totally different reference points. She recommends that unless you are working with the same or similar cultures, stick with low context communication.

Chapter 2: Providing Feedback: Direct vs. Indirect Feedback

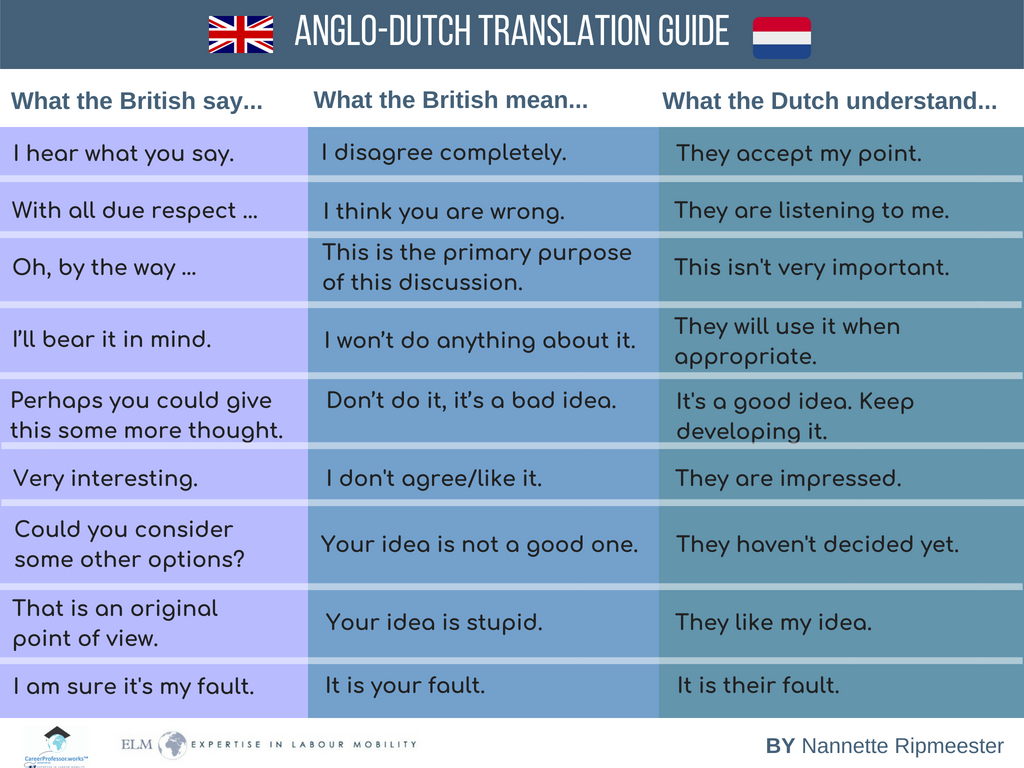

Some cultures, like the Dutch, are very direct in their criticism, bluntly saying what they think. Others are more indirect in their criticism, such as the Japanese. In many ways, this is tied to high versus low context cultures, but not always - for example Russians are very direct in their feedback but are a higher-context culture. (note: this only applies to a boss giving feedback to a subordinate, not the other way around)

To other cultures, Americans seem particularly absurd, because while we are low context and more direct, we have a “weird” feedback culture where we accentuate the positive rather than the negative. In France on the other hand, the negative is emphasized rather than the positive. So when a compliment is given, it’s high praise indeed. She cites as an example a French woman who worked in Chicago, and thought she was doing a good job because us “direct” Americans mostly said good things about her. The negative things noted about her in performance reviews seemed minor to her. In reality, she was close to being fired for sloppiness in her work.

She recommends not trying to imitate the directness of a direct culture if you find yourself in one. Just because they are direct, doesn’t mean it’s impossible to be rude in that culture, and you, as a foreigner, are unlikely to understand those subtleties. She gives an example of a Korean in the Netherlands who tried to imitate the Dutch directness and got a reputation as aggressive and difficult to work with. So don’t do that. Instead, try to be balanced in your positive versus negative criticism and be mild when giving feedback.

She also recommends when communicating feedback with indirect cultures to never give individual feedback in front of a group - this includes positive feedback. Instead, give it only in 1-on-1 sessions, preferably over food and drink. She also recommends avoiding giving negative feedback, and to soften the message. For example, she gives an example of critiquing a series of documents to an Indonesian colleague. Two of the documents were very good, but two others were obviously finished in a rush. Instead of saying the two documents were bad, she said what was right about the two good documents. He got the message and corrected the two bad documents.

Chapter 3: Why vs. How vs. Holism

This chapter starts with an example of an American automobile research engineer going to Germany to give recommendations to an auto supplier on how to cut costs. She starts with her recommendations and case studies showing the success of these recommendations, but the Germans start immediately asking questions like “how did you get to these results?” She found the presentation that she had worked so hard on falling on deaf ears, but she had given these presentations in America and they worked fine. What gives?

Anglo cultures are Applications-First cultures, where the practical applications of an idea are focused on first, then the theory underpinning it. Continental European and Latin American cultures in contrast, are Principles-First cultures: you learn the theory first, then apply it. One example she gives is math class: In France, students are taught to calculate pi as a class before using it in a formula. Americans, on the other hand use pi in a formula first, then learn how it’s derived. When trying to persuade an applications-first audience, make sure to lead with your key points and use case studies to persuade them. Make your argument short, or else you will lose the attention of your audience. If you’re working to persuade a Principles-first culture, start with your premises, and build up your argument to a conclusion. Include possible counterarguments and your responses to them. If working with an audience that consists of both cultures, start with case studies to grab the attention of an applications-based audience, show how they are examples of a general theory for your principles-based audience, then give your recommendations after explaining the theory.

However, this advice only applies to European cultures - Asian cultures are Holistic: they focus on relationships and the whole picture, rather than each individual part of the picture. For example, some researchers gave an American and Japanese focus group a task: Take a portrait picture of a person. The American’s portraits were all close-ups of the face of the subject, while the Japanese took a picture of the entire body, showing the subject in their surroundings. Holistic cultures find western (“specific”) cultures make too much effort to isolate a small part of the picture without considering the interdependencies of each part. Specific cultures feel that holistic cultures take too long to get to the point, describing a large amount of extraneous detail. When managing a holistic team, don’t give each individual specific segmented information. Instead, start with the big picture and how each part of the effort fits into the whole.

Chapter 4: Egalitarianism vs Hierarchy

This chapter starts with Jepsen, a Danish manager at Maersk. In Denmark, there is an extreme sense of egalitarianism. The boss is addressed by his first name, and the intern’s voice in meetings has just as much impact as him. He gives his subordinates objectives, and the power to implement those objectives as they saw fit. He was promoted to President of a Russian office outside St. Petersburg, and found himself for the first time having trouble managing his staff.

His complaints about his Russian staff:

- They call me Mr. President

- They defer to my opinions

- They are reluctant to take initiative

- They ask for my constant approval

- They treat me like I am king

His Russian staff’s complaints about him:

- He is a weak, ineffective leader

- He doesn’t give us direction

- He gave up his corner office on the top floor to work with us, suggesting our team is of no importance

- He is incompetent

The disconnect was because Russian culture is more Hierarchical than Denmark: they show respect for the boss, the boss’s opinions are followed, even when they think the boss is wrong.

When managing a more hierarchical culture:

- Your team members may not speak unless explicitly told to do so, and even then may hesitate to answer. A few days before a meeting, set the expectations for the meeting, what questions you will ask.

- Ask your team to brainstorm ideas without you, then list what they brainstormed to you - this helps remove their need to defer.

- Communicate with the people at your level in hierarchy, and get explicit permission to skip levels.

- Address people by their last name and title.

- Avoid giving up symbols of authority and keep in mind their importance.

When managing a more egalitarian culture:

- Manage by objective: give your subordinates concrete objectives that you negotiate with them and let them complete them on their own initiative. You can consider having bonuses or other incentives attached to these objectives.

- Think twice before copying the boss on an email. Doing so may suggest you do not trust the recipient.

- Use first names when sending emails.

Chapter 5: Big D and little d Decision Making

In this chapter, she starts with a merger between an American and German financial company. The Americans described the Germans as too hierarchical, with a focus on titles and chain of command. The Germans in turn thought the Americans were too hierarchical - the boss said turn left and everyone turned in unison.

This disagreement happened because Germany is more Consensual (Big D) in decision-making - decisions are made by groups in unanimous agreement. Once consensus is reached, it is final. In contrast, the US is a Top-Down (Little d) decision-making culture. Decisions are made by individuals and propagated downwards, but they are not final - decisions are flexible and may be changed.

Another example of consensus-driven decision making is the ringisho management system in Japan, which manages to be bottom-up, hierarchical and consensus driven at the same time. The lowest level managers write a proposal, and circulate a document among themselves. Each manager adds comments and their stamp of approval. Once all the managers agree, the document is sent to the next highest level, who repeat the process until it reaches the top of the organization, where it is given final approval.

When working with a more consensus based culture:

- Be patient with the decision making process. It will take longer, involve more meeting and correspondence.

- Check in with your counterparts regularly to show commitment and availability to answer questions.

- Keep a pulse on the team to make sure a consensus is not forming without your participation.

- Don’t push for a quick decision. Once a decision is made, it is hard to change it.

When working with a more top-down culture:

- Expect decisions to be made with less input from you.

- Be ready to follow a decision that is made.

- If you are in charge, solicit other viewpoints, but make decisions quickly. Otherwise people may view you as indecisive and an ineffective leader.

- If there is no obvious boss, suggest voting to make a decision that is committed to.

- Remain flexible - decisions may not be final.

Chapter 6: Building Trust

The author introduces the chapter with a merger between an American and Brazilian steel firm. The Brazilians were invited to Mississippi to meet their American counterparts, where they had meetings all day, then retired to their hotels. However, while the Americans thought the merger was going well, the Brazilians did not. The Americans were then invited to Brazil, where they had long lunches and dinners. While the Brazilians were happy to get to know their American colleagues, the Americans were concerned nothing was getting done. This disconnect illustrates the difference between Task-Based cultures, such as the United States and Switzerland, where trust is formed by doing business work together and establishing your competence, and Relationship-Based cultures such as Brazil and China where trust is formed by building interpersonal relationships.

This contrast is shown in how we approach our interpersonal relationships in and out of business. For example, in Spain, if a colleague loses their job, they keep up their friendships with their fired colleagues. In America, we rarely contact our colleagues after they leave the company. In Asian cultures, if you fire a salesperson, the clients they had a relationship with may also leave. Other cultures can find that the Americans are more upfront and friendly, but it’s a superficial friendship. One Russian recounts a story of meeting an American on a plane and having a deep conversation with him. They never met up again, and the Russian felt betrayed by that - that he had opened up to someone who was not a real friend.

Recommendations:

- Don’t consider going out for drinks or long lunches a waste of time.

- When going out, you aren’t going as your business self - show your true self.

- Find common interests between you and the person you are attempting to form a relationship with.

- Don’t email someone out of the blue, instead look for a mutual friend to introduce you.

Chapter 7: Disagreeing Productively

The French are much more likely to disagree openly than Americans, who in turn are much more likely to disagree than the Japanese. In addition, some countries are much more expressive than others - she gives an example of Saudi Arabia where her driver got into a 10 minute conversation where both participants yelled, had expressive hand gestures, and seemed angry. When she asked what the argument was about, he said he was asking for directions to her hotel! However, while expressive, Saudi Arabia is an example of where disagreement is done in private rather than openly - disagreeing may damage your relationship with the other person.

Another example she gives is surveys on meeting styles:

- Americans are much more likely to think that a productive meeting is one where a decision is made.

- The French think a productive meeting is one where various viewpoints are debated.

- The Chinese and Japanese believed meetings were for putting a formal stamp of approval on a decision already made.

I’m interested if these various styles have implications for how politics is done in these countries.

When working with more confrontational cultures:

- Accept disagreement - it’s a sign of interest in what you are saying.

- Don’t try to mimic their confrontational style - you can still be rude in an unfamiliar culture.

When working with less confrontational cultures:

- Have meetings before the meeting where subordinates prepare so they don’t feel put on the spot in a meeting.

- Avoid disagreeing with the boss openly, and accept that subordinates will not disagree with you.

- Use one-on-one meetings to gather feedback rather than risk disagreement in front of a group.

Chapter 8: How Late is Late?

She gives an example of Nigerians working with Germans. The Germans wanted to schedule everything months in advance, while the Nigerians living in the muslim north of Nigeria wouldn’t know when their holidays started until the Mufti looked at the moon and decided today was the start of holiday. There was a lot of mutual frustrations on both sides of this relationship, with each thinking the other culture’s way of doing business was inefficient and stressful.

Some cultures are Linear-time: They value organization and adherence to pre-planned schedules. Others are Flexible-Time: they are less strict about punctuality and are more flexible in response to changing demands. An example of flexibility is China, where if you call the plumber, the plumber may show up five minutes later, so you’d better be prepared for them.

When working with a linear-time culture:

- Don’t cut in line.

- In meetings, expect the agenda to be strictly followed.

- If given 60 minutes for a presentation, try not to go over the allotted time.

When working with a flexible time culture:

- Don’t be surprised if people don’t queue orderly in the way you expect.

- In meetings, if there is an agenda, it will be loosely followed.

- If given time for a presentation, you may go over time if the audience is interested in more.

- Expect to adapt to changing requirements.

Conclusion

There’s a joke: two young fish are swimming. An older fish comes along and asks the young fish “How’s the water?” The young fish ask: “What is water?”. Our own culture can often seem as invisible to us as air or water to fish. This book not only provided a valuable explanation of other cultures, it also explained my own American culture to me.