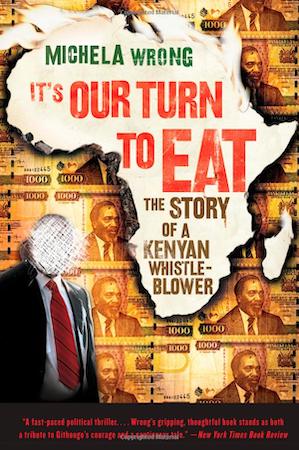

It's Our Turn to Eat: Corruption in Modern Kenya

This 2009 book by Michela Wrong is about John Githongo, a Kenyan anti-corruption crusader. He is invited to be the Permanent Secretary for Governance and Ethics in the new presidency of Mwai Kibaki. He quickly realizes that his position is to create the appearance of doing something about corruption, not to actually do anything. He discovers a scandal that goes all the way to the top that he is explicitly discouraged from investigating. But instead of giving up, he secretly records his colleagues’s and leaks it to the press.

A Brief History of Kenya

Kenya was colonized in order to build a railway to connect existing British colonies in Africa. At first the interest was just in a railroad. Nairobi, was just where the British happened to decide to build a rail depot. But the rail company went bankrupt and was nationalized. The British decided that in order to make up their investment they needed to develop the land around the railroad, and established the Kenya Colony in 1920. The various tribes of Kenya were forcibly settled onto ethnic “homelands”, with the best lands reserved for whites. Export of cash crops was limited to white settlers. The effect of this was to divide Kenyan society by tribe - tribes stopped intermingling and trading. The British also hired each tribe for specific jobs- Kikuyu to be household help, Luo to be miners etc; This would later contribute to Kenyan politics being fractured on tribal lines, and created the stereotypes each group has about the others. The British also had a large number of Asians from India come in to work as railroad laborers, who became the finance/business/trader class of Kenya. The Kikuyu (the largest tribe in Kenya) - especially resented this arrangement especially because they were farmers and the British had taken the best farming lands as well as lands traditionally settled by them. This led to the Mau Mau Rebeliion, which the British eventually put down. However, it was really more of an internal civil war among Kenyans, than an anti-colonial independence struggle. The struggle was between the Mau Mau independence fighters, and the collaborator “Home Guards”, both sides being Kikuyu. There were 252 white settlers killed, and over 20,000 Kenyans killed. While the British eventually crushed the rebellion, it was enormously expensive and the British decided to give Kenya independence in 1963.

After independence, Jomo Kenyatta became president. He instituted a system called “eating” - where the dominant tribe would suck up the national tax revenue and prioritize benefits to their tribe. This led to extreme inequality. For example, in 2009, a Kikuyu can expect to live 23.4 years longer than their Luo counterparts, due to better doctors. In an effort to detribalize Kenya, land resettlement programs were created but most of the land was granted to Kikuyu cronies of Kenyatta. So the Kikuyu spread out across Kenya, but the other tribes stayed in their homelands.

This changed when Jomo Kenyatta died and the VP Daniel Moi, a Kalenjin, took over. He instituted more “eating” - but this time it was the Kalenjin’s turn to eat. He would rule 22 years in Kenya, his handpicked successor defeated in the first multi-party elections in Kenya.

Mwai Kibaki succeeds Daniel Moi. This is seen as a great moment for Kenya - the first time power transferred peacefully through a fair election in the country’s history. He also gives a speech at the inauguration saying that the old ways of doing things were over, that corruption would end in Kenya. He’s referring to scandals such as Goldenberg, where 10% of the countries GDP was lost to embezzlement by elites. Goldenberg was a phony company that was supposedly exporting gold to Britain that served as the shell company behind the transactions. He appoints John Githongo, the founder of Transparency International in Kenya to lead the efforts to clean up corruption.

Kibaki is a Kikuyu, but also makes some effort to broaden his coalition beyond the traditional Kikuyu-Meru-Embu alliance and puts more diversity in his cabinet as well. However, 3 months into Kibaki’s presidency, he has a stroke - and is not the same person afterwards. He has trouble concentrating, and starts to rely more on Kikuyu assistants rather than his initial cabinet.

Enter John Githongo

He’s a Kikuyu - and that was why he was still trusted after Kibaki’s stroke. His father was the personal accountant of Jomo Keyatta. He was taught in one of Kenya’s elite schools, St. Marys which while not the best of the best schools, it focused on developing an attitude of public service among its attendees. However, he appalled his family when he decided to pursue a journalism career rather than take on the family firm. He was popular but flaky, and so well known for not showing up to parties he said he would come that it was said you got “Githongo’d”

It quickly becomes clear that Kibaki wants to investigate corruption that happened under the Moi administration, not what’s going on in his. John takes on his job with gusto however, and develops a network of informants who feed him information about something called “Anglo Leasing” - a mysterious British company that the Kenyan government contracts with to buy helicopters, a modern crime lab, passport printers, etc at wildly inflated prices. And Anglo Leasing didn’t seem to be anything but an address in London. Initially it appears to Githongo that this was a Moi administration deal, but is later told by the president’s aides to back off. After John persists, he is demoted by the administration. John appears to back off, but starts following up with his informants, and starts recording his conversations with government aides. They, thinking he is tamed, start openly boasting of their schemes to embezzle the countries money with him.

He captures enough information and resigns unexpectedly, causing a stir in Kenyan politics. Intelligence services try to keep him from leaving, but one step ahead he flees, to Britain. There he assembles a dossier on the Anglo Leasing scandal and wants to reveal it to the Kenyan parliament. However, he is afraid that he will be arrested under Kenya’s Official Secrets Act if he returns home. So he invites the Parliamentary Anti Corruption Committee to Britain so he can testify, and they do send one member there. However, when he “testifies” he is later told the tape recorder was broken for multiple days of testimony, and is passed a death threat towards him and his family if he continues. Undaunted, he feeds the dossier to Kenya’s best newspaper The Nation.

The scandal fascinates the country, with weeks of coverage dedicated to it and it looks like high level cabinet members will be fired and prosecuted. However, the powers that be soon find their balance again and start attacking John. John is branded a traitor to the Kikuyu, and Kenya’s smear press gets to work making up allegations such as being caught at a gay orgy. You’d think he’d be liked among the non-Kikuyu but that wasn’t true either - sure he was one of the good ones, but he was still a Kikuyu.

2007 Elections In Kenya

Meanwhile, the 2007 elections are underway in Kenya. There was a lot of ethnic tension leading up to the election. For example, Kibaki promised a new constitution for Kenya but pretty much put lipstick on the old one, with its super powerful presidency and little role for parliament. Voters rejected this constitution on mostly ethnic lines, which put fear in the Kikuyu they may lose the next presidential election. Leading up to the 2007 election, the Luo were “we have to win this election” and built a coalition of all the left out tribes of Kenya. The Kikuyu, meanwhile were “we can’t lose this election”.

Ominously, hardware stores notice a sudden surge in the sale of machetes, to the point where they have to restrict them to 1 per customer, and police find armed men suddenly being transported in vans across the country.

The December 2007 elections seems to go by smoothly. People line up to vote, votes are cast and counted. The country settles in to see the results. The parliamentary elections favor the Luo - they win a resounding victory. But results for the presidential election are not coming in. People wait breathlessly for the results. Then late at night the results come in - and Kibaki etched out a narrow victory. The Luo are outraged, certain that the election has been fixed. Gangs come out and find the nearest Kikuyu family and kill them, burn their house down, etc; Kikuyu soon start forming rival gangs and kill the first Luo or Kalenjin they see. People flee for their ethnic homelands, the slums of Nairobi are burned down. The author was reporting for the Financial Times then, and she describes being trapped in a hotel and describes how her hotel was ignored because it belonged to a member of the Luo, but the stores nearby were looted - people knew exactly which businesses belonged to which ethnic group. At the end of this, 1500 Kenyans are dead, and 600,000 displaced.

Eventually, the politicians negotiate a deal - Kibaki agrees to share power with a prime minister of parliament, and things settle down. This time everyone gets to eat - they establish a huge multi-ethnic coalition that was so big the pork required to sustain it was 80% of government revenue. But all talk of Anglo Leasing or John Githongo is gone. He is allowed to return to Kenya, forgotten. Corruption is forgotten. A country that once thought it had put tribal prejudices behind them now realizes that tribe is everything in their society. The economy is in shambles, and tourism has dried up.

Conclusion

Something that I didn’t mention in this review is the author’s ambivalence towards the NGOs that provide corrupt African governments with cheap loans and aid - they say they want transparency and stronger measures against corruption, but do very little to hold them accountable. Some of them are actively involved in the corruption, or have conflicts of interest. For example, multiple World Bank directors for Kenya lived in mansions owned by the president at very low rents. She sees the NGOs as too focused on shoving aid out the door - you aren’t promoted for denying projects for corruption concerns, you’re promoted for getting money out the door. However, she admits that if they didn’t provide the aid, it’s likely the politicians would steal before building schools and hospitals the aid is built, so there’s not a lot they can do.

She recommends think that European countries copy America and make it a crime to bribe someone in a foreign country. And that Britain should look into why so many African countries are allowed to have shell companies for procurement fraud registered in the UK.