Boss: The Life and Times of Richard J. Daley of Chicago - Part I

This is Part 1 of a three-part series on Richard J. Daley

Part II: Mayor

Part III: American Pharaoh

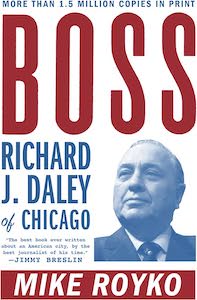

Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. By Mike Royko. 216 Pages.

American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley - His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. By Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor. 624 Pages.

Richard J. Daley was perhaps the most powerful local politician America has ever produced. The second most powerful politician in America after the president, he personally selected every Democratic candidate running in Illinois, from Governor to Alderman. In addition to the elected positions, Daley controlled forty thousand patronage jobs, from judgeships down to the ditch diggers; he personally selected who got those jobs. Beyond the borders of Chicago, Daley played kingmaker for the Democratic nomination for president; his ability to control the Illinois delegation made and broke presidential candidates.

What were Daley’s goals? First and foremost, to amass and maintain his personal political power. When it came to ideology, he had a sort of flinty conservatism: he liked authority and hated protestors. He was a devout Catholic, going to mass every day. He regarded the newspapers and reporters as the enemy, always criticizing, always asking questions. He believed in racial segregation and that people should pull themselves up by their bootstraps. But good politics came before ideology with Daley; his concern was always what would be best for him and the machine. Daley did not like John F. Kennedy’s liberalism, but he did like that an Irish Catholic presidential candidate would turn out the machine base on election day. And so he backed him for president.

Daley was not an articulate man, known for malapropisms such as “The policeman isn’t there to create disorder; the policeman is there to preserve disorder.” and “Today the real problem is the future.”. When questioned by reporters or opponents he was known to fly into fits of rage, and rant at them:

If provoked, he’ll break into a rambling, ranting speech, waving his arms, shaking his fists, defending his judgment, defending his administration, always with the familiar “It is easy to criticize . . . to find fault . . . but where are your programs . . . where are your ideas . . .”

Arrogant and ruthless, he always got what he wanted - and if he didn’t, he would make sure you would never hold an office or job in Chicago again. And yet for all his flaws, Daley saved Chicago from going the way of other declining rust belt cities, like Detroit or St. Louis. Historians have ranked him amongst the greatest American mayors of all time.

This is the story of the last of the big machine bosses.

American Pharaoh is a 600 page tome on the life and times of Richard J. Daley. It’s impressively researched, but a bit dry at times. The book takes it’s title from the African-American nickname for Daley: “Pharaoh”. To them he was an oppressor, demanding much of his subjects but offering little in return.

Boss is the much more fun read, written by Chicago Tribune humorist Mike Royko. While it is not as impressively researched, I like the style it is written in more, peppered with observations such as:

Daley didn’t come from a big family but he married into one, and so Eleanor Guilfoyle’s parents might well have said that they did not lose a daughter, they gained an employment agency. Mrs. Daley’s nephew has been in several key jobs. Her sister’s husband became a police captain. A brother is an engineer in the school system. Stories about the number of Guilfoyles, and cousins and in-laws of Guilfoyles, in the patronage army have taken on legendary tones.

A City of Neighborhoods

Early 20th century Chicago was a “City of Neighborhoods”, each with its own ethnic group: Germans on the North Side, Irish on the South Side, and Jews on the West Side. People kept to their own kind, and outsiders entered other neighborhoods at their peril.

Richard Joseph Daley was born in the Irish neighborhood of Bridgeport in 1902. Bridgeport was Chicago’s original slum, a grim place even by the standards of early Chicago. Irish laborers settled it in the early 1830s, digging the Illinois & Michigan Canal. After the canal was finished, the neighborhood turned to animal slaughter. By the time Daley was born, the Irish were prospering and no longer treated with the discrimination their parents and grandparents encountered upon arriving in America. But Daley was raised with stories of the famine and discrimination, and that would be his common refrain when civil rights groups asked him for change: “The Irish were discriminated against, and we pulled ourselves up by our bootstraps. Why can’t the Blacks do the same?“.

Daley spent his free time at the clubhouse of the Hamburg Athletic Club, which was part social club, part intramural sports team, and part street gang. Youths in the Hamburg Athletic Club policed the borders of the neighborhood, ensuring no outsiders entered, especially African-Americans living in the encroaching ghetto east of Wentworth Avenue. Poet Langston Hughes made the mistake of crossing the invisible boundary his first weekend in Chicago and was beaten by an unknown Irish street gang.

The Hamburg Athletic Club became infamous for its role in instigating the 1919 Chicago race riot. Started when an African-American swimmer drifted into the white beach area, the riot lasted for a week and killed 38 people. Later, gangs such as the Hamburg Athletic Club were found to have spent the entire summer trying to start a riot and actively attacked black neighborhoods when clashes started. Daley was always shifty about his memories of the riots, refusing to say if he participated or not. This was political calculation; Daley needed both white and black votes, and saying nothing allowed them both to believe he was on their side in 1919. But it should be noted that the youths of the club thought highly enough of Daley that they elected him their president at the age of 22, a position he retained for fifteen years.

A House for All Peoples

The Hamburg Athletic Club was also Daley’s introduction to politics. Chicago’s athletic clubs were sponsored by local ward bosses, and members often served as political workers, getting out the vote in campaign season. The 11th Ward Alderman and Ward Committeeman, Joseph (“Big Joe”) McDonough took an interest in Daley, and made him his personal assistant in the 11th Ward Organization. Daley had been inducted into Machine politics.

The Chicago Machine - formally known as the Cook County Democratic Organization - dominated Chicago politics. While ultimate authority rested with the County Chairman, it was the Ward bosses (Committeemen) who did the day-to-day work of slating candidates for office, distributing patronage and dispensing favors. Daley was one of three thousand precinct captains spread out over Chicago’s fifty wards. Precinct captains were responsible for forming personal relationships with four to five hundred voters, and were expected to predict vote totals within ten votes. Ward bosses and captains who failed to deliver on election day were “vised” and replaced with someone who would do better.

The Machine ethic could be summarized in ten rules, according to one academic:

- Be faithful to those above you in the hierarchy, and repay those who are faithful to you.

- Back the whole machine slate, not individual candidates or programs.

- Be respectful of elected officials and party leaders.

- Never be ashamed of the party, and defend it proudly.

- Don’t ask questions.

- Stay on your own turf, and keep out of conflicts that don’t concern you.

- Never be first, since innovation brings with it risk.

- Don’t get caught.

- Don’t repeat what you see and hear, or someone might get indicted.

- Deliver the votes, or we will find someone who will.

The political machine that Daley would one day inherit was an invention of Czech leader Anton Cermak. Cermak had wrested control of the machine from the Irish by uniting the various immigrant groups in Chicago under one issue: Prohibition. Protestant native-born Americans tended to favor Prohibition, and immigrants saw the attacks on alcohol as an attack on them. The Irish initially resented this Bohemian upstart, but by creating the pan-ethnic ticket, he had strengthened the machine enough to take on the current mayor, Republican William “Big Bill” Thompson. Cermak won the mayorship, but for only a short time: in 1933 he was slain by a bullet meant for FDR while vacationing in Florida.

Daley’s patron, Alderman McDonough, had been slated for County Treasurer by Cermak, who brought Daley along as his deputy. McDonough was not a man given to hard work or details, and he left the job to his deputy. However, Daley was not satisfied with running the Treasury and wanted to move up in the world. The trouble was, all of the slots Daley could conceivably move into were taken. Worse, McDonough’s power had waned with the assassination of Cermak. The Irish had reasserted their dominance, and the former allies of Cermak were being pushed out. Patrick Nash took over the machine and slated Edward Kelly as mayor.

McDonough unexpectedly died in 1934. While having your political patron die was usually a death knell for your career, Daley was known as a bright star in the machine. He quickly allied with the Kelly-Nash faction and stayed in his role as deputy County Treasurer, but was not slated for 11th ward boss, much to his disappointment. However, Daley’s lucky streak continued - politicians continued to die at a young age, and one of the three state representatives for Bridgeport died. This man was a republican, elected as part of a deal to send two Democrats and one Republican to Springfield. The Republicans attempted to select their own man, but the Democratic-controlled state election board ruled it was too late to reprint the ballots. The machine organized a write-in campaign for Daley, who was duly elected as state representative. Daley had won his first office, but as a Republican.

Springfield

The Springfield that Daley arrived at in 1936 was corrupt, even by the standards of early 20th century America. Most legislators were there for “girls, games, and graft”. The most common kind of bill was a “fetcher” bill, a bill designed to harm the many special interests that sent lobbyists to Springfield. Lobbyists came over with envelopes of cash, and the bill was quietly dropped. If directly taking money from lobbyists was too much for a legislator, lobbyists hosted card games guaranteeing winnings of up to one thousand dollars. Daley personally was never on the take, never drank, and never cheated on his wife. He instead holed up in his hotel room with draft bills and budget documents.

Even if he wasn’t corrupt, Daley was a machine man, and considered his primary job to do the bidding of his masters in Chicago. However, he was also a surprisingly progressive force: he attempted to create income and corporate taxes to replace the regressive sales tax, introduced bills to strengthen tenant protections, and was an early supporter of the school lunch program. His greatest accomplishment in Springfield was creating the Chicago Transit Authority out of the ashes of the bankrupt transit companies. Of course, many of the bills were designed to promote the machine’s interests:

One Daley tax reform, which he tried to pass four times, would have allowed Cook County residents to appeal their tax bills directly to the county assessor, rather than proceed through the court system. It might have made appeals simpler for taxpayers, but its greatest beneficiary would have been the ward committeemen and aldermen who could then use their ties to the highly political county assessor’s office to reduce the taxes of their friends and supporters. Daley was also doing the machine’s bidding when he crusaded to revise the state’s divorce laws to make the state’s attorney part of every divorce. The change would have given the state’s attorney’s office a five-dollar fee for every divorce action filed in Cook County, generating revenue and work for an office that was usually filled by the machine and that employed an army of Democratic patronage workers.

Daley acquired a reputation as an expert in budgetary matters and was promoted to State Senator, then elected the youngest Senate Minority Leader in Illinois history. In the Chicago tradition of double-dipping, he was given the job of Cook County Comptroller. In addition to giving Daley another salary, this was a particularly sensitive post since he could see the books of the entire county. Daley knew which contractors were favored, which contracts that were “lowest bid” were secretly loaded with extras, and who was given what job. A person who drove a politician around might be employed as an engineer for the Highway Department. Anyone who could read the figures knew where the bodies were buried.

After a decade in Springfield, Daley was ready to return to Chicago. At the same time, Mayor/Boss Edward Kelly was in trouble. He had proved too corrupt even for Chicago, and voters were ready to throw the machine out. Worse for his political prospects was his support for racial integration. Kelly needed a slate of candidates who seemed reform-minded but could be counted on to advance the machine’s interests in office. Daley seemed the perfect choice: he had a reputation for honesty and hard work, but completely loyal to to the machine. Kelly slated him for Cook County Sheriff.

If the office of sheriff was good for the machine, it was hard to see it as good for Daley. The sheriff’s office was the most corrupt of offices, and considered a career-ender. The Sheriff’s office patrolled unincorporated Cook County, and was empowered to enter Chicago and the suburbs if the municipal police weren’t doing their jobs. In reality, they spent most of their time shaking down motorists, suburban bars, and brothels. A journalist remarked that if a Sheriff hadn’t cleared $1 million ($18.5 million in 2024 dollars) in his four years in office, he wasn’t trying. Few left without being the subject of scandal, and most simply tried to clear as much money as possible before ignominious retirement. Daley’s mother remarked “I didn’t raise my son to be a policeman”.

Unfortunately (or rather, fortunately) for Daley, the 1946 elections were a disaster for Democrats. President Truman’s approval ratings had slid to 32% amid high inflation and shortages. The Democrats were trounced in the elections, and Daley lost to his Republican opponent. The loss wasn’t held against him because the entire slate had been defeated. Daley never had to tempt his ethics.

Boss

Daley also had his eyes on the 11th Ward Committeeman position. After McDonough passed, the 11th Ward Alderman and Committeeman seats passed to Daley’s new patron, Hugh “Babe” Connelly. However, Connelly’s health was failing, and he lost his alderman seat to a Republican in the 1946 disaster. Daley convened a meeting that Connelly was too ill to attend and struck a deal with the Poles moving into Bridgeport. They would support Daley for Ward Boss, and he would support a Pole for the aldermanic seat.

Daley now had a seat in the Cook County Democratic Central Committee, the politburo of the machine. The Central Committee is a collection of all the committeemen from the Chicago wards and Cook County suburbs. However, it is not a committee of equals; each member votes in accordance with how strong the Democratic vote was in the last election in their ward. Daley, coming from the heavily Democratic 11th ward, was one of the most powerful members on the committee.

Meanwhile, Kelley had resigned as party boss, but Irish factions in the machine were divided on who to replace him with. They settled on Jacob Arvey, committeeman from the Jewish 24th Ward. Arvey was an ideal caretaker because the Jewish vote was relatively powerless, and he would not be able to seize control of the machine. He, however made some clever slating decisions and over-performed expectations. His first decision was to slate Martin Kennelly, a reform-minded Democrat, for mayor. While there was a risk in slating a reformer for a city-wide office, where they might actually do something, it was better to have a Democrat they could remove than a Republican they couldn’t. More importantly, he was opposed to racial integration. Arvey next slated Adlai Stevenson for governor and Paul Douglas for US Senator, other great reformers. Having reformers at the top of the ticket boosted down-ballot races, but at the same time these offices controlled less patronage and could not do much damage to the machine. The strategy worked brilliantly, and Arvey was kept on as caretaker. However, Arvey’s luck ran out when he slated police Captain Daniel “Tubbo” Gilbert for Sheriff. Gilbert had claimed to a Senate crime committee that he had accumulated a fortune of $360,000 ($4.6 million in 2024 dollars) by being a successful gambler, and when asked if his gambling was legal, replied “Well, no. No, it is not legal.”. The testimony was leaked to the Chicago Sun-Times days before the election, and headlines proclaimed the “World’s Richest Cop”. The Democratic ticket went down in flames, and Arvey was blamed:

Chairman Arvey, hailed as the genius who saved the Machine by slating Kennelly, Douglas, and Stevenson, was now the idiot who slated Tubbo Gilbert. In the silence of the Morrison Hotel headquarters, Arvey waited for somebody, anybody, to tell him it was just one of those bad breaks and not to worry about it. Arvey, knowing he was being blamed, was hoping for a vote of confidence. Nobody offered it, so he finally said, “I think I’m going to resign.” Then he went to California to take a vacation and wait for somebody to call and ask him to change his mind—Joe Gill, Al Horan, Daley. Nobody called, so that was it; he was out.

Daley headed up the Arvey faction now, but when the votes were tallied, neither he nor his rival, 14th Ward Committeeman Clarence Wagner, had enough votes to secure the chairmanship. The two factions were less divided by policy than personality: Daley’s faction was the richer Irish, referred to as the “lace-curtain” Irish, and resented by Wagner’s faction for looking down at their less-successful brethren. The two sides settled on Joseph Gill as interim chairman until 1952. Both sides regarded him as neutral, and as the oldest member of the committee, unlikely to stay on long. 1952 came to pass, and Daley had accumulated barely enough in patronage and votes to take the chairmanship. Hover, Wagner was not ready to concede, and proposed the committee break for two weeks to stall for time and consolidate his position. Wagner took a group of influential politicians up to Canada on a fishing trip, where he died in an automobile accident. Even for a career built on well-timed deaths, no death in Daley’s life had been more convenient than this. He had the chairmanship; The next step was the mayorship.

Kennelly

Kennelly was shaping up to be a mediocre mayor, content mostly to attend ceremonial functions and do little else. Unfortunately for the machine, the one issue he took on with gusto was civil service reform. While Chicago, in theory, had civil service protections, the machine had ways of getting around it. Exams were held so infrequently or made so difficult that nobody was available to be hired the honest way. The city could then hire political flunkies as “temporary” employees, many of whom spent their entire careers as temporary hires. Kennelly started running exams again and consolidated titles so that they fell under civil service protection. The ward bosses lost 12,000 jobs over Kennelly’s mayorship and were ready to remove him.

Kennelly also went too far on the race issue. While he was slated because he was against integration, a careful balance needed to be struck. One of the innovations of the Kelley-Nash machine was to bring in the black vote. African-Americans had traditionally voted Republican, the party of emancipation, but this changed with the advent of the depression and FDR’s New Deal. Kelley eagerly took up federal funding the New Deal, and distributed patronage and welfare to a black sub-machine controlled by Congressman William Levi Dawson.

Like most politicians, Dawson’s main concern was his own political power and was a loyal machine man. He opposed integration because spreading out the black vote would dilute his power, and the machine was against it. In exchange, he promoted welfare politics for his constituents. While he didn’t get as much patronage as white politicians, he got his share of jobs and favors and was an influential power player in Cook County.

during the 1960 presidential campaign, Dawson served on the civil rights issues committee of John F. Kennedy’s presidential campaign — known as the Civil Rights Section. The first thing Dawson tried to do was get the name changed. “Let’s not use words that offend our good Southern friends, like ‘civil rights,’” he told the group’s first meeting. His office in the campaign headquarters was quickly dubbed “Uncle Tom’s Cabin.” Dawson’s primary loyalty was to his political organization, not his race — and when the two were in conflict, the Democratic machine always won. “You would not expect Willie Mays to drop the ball just because Jackie Robinson hit it,” Dawson liked to say.

Dawson’s ability to deliver 70 percent of the vote in his three wards was critical to the machine’s lopsided victories. Kennelly, however, had forgotten who had elected him and began a moralistic crusade against two black institutions: “policy wheels” and “jitney cabs”. “Policy” was a popular gambling game, similar to the modern day lottery. Thousands of policy stations were spread throughout the South Side. While technically illegal, Dawson personally selected the police officers who served in his fief and ensured they did not prosecute the policy wheels. When the Chicago Outfit attempted to bribe a police captain into letting them muscle in on the action, Dawson had him replaced.

“Jitney Cabs” was the Chicago term for unlicensed taxis that operated in the South Side Black Belt. Licensed taxis were exclusively controlled by white operators and only traveled to white neighborhoods. Jitney cabs were a lifeline for the African-American community, which was not served by public transportation. Dawson was therefore shocked when police officers from downtown started arresting policy wheel operators and jitney drivers. Dawson was traditionally given a free hand to determine what illegal activities were allowed in his neighborhoods. Many blacks saw it as thinly-veiled attempt to let the white Outfit profit from their communities. And Kennelly wasn’t improving welfare or leaning on slumlords to clean up their properties; - just attacking the things they liked and needed.

Dawson went to Kennelly, and explained the situation. Kennelly, however refused to do anything, and insulted Dawson at the same time. Dawson didn’t ask again, and instead plotted his revenge. When it came time to re-slate Kennelly, Dawson made a surprise appearance from Washington and dressed Kennelly down:

“Who do you think you are? I bring in the votes. I elect you. You are not needed, but the votes are needed. I deliver the votes to you, but you won’t talk to me?”

After the tirade and Kennelly was thoroughly chastised, the party admitted that Kennelly’s civil service reforms made him too popular; the machine would be forced to run him again. But he would not get another term after this one. This deal was made in the backrooms of the Central Committee, and Kennelly was unaware such a deal had taken place. Daley began quietly building a case for him to take over as mayor and freezing out Mayor Kennelly from the organization. Daley stopped inviting Kennelly to party functions or asking his opinion about slating decisions. Kennelly, however failed to get the message and was shocked when he was not re-slated in 1954. The slating committee instead picked Daley, who pretended to be surprised. The official line was that Daley had been drafted, not seeking the office.

The Primary

Despite not getting the Democratic endorsement, Kennelly was not going to let go of city hall without a fight. He entered the primary determined to win a third term in office, showing a fire he had never exhibited as mayor. Kennelly fired all of the ward leaders who had voted against him from their patronage positions, and also vowed to fire any city employee who campaigned against him. He received the backing of Chicago’s business community, who made sizable campaign contributions. Most importantly, he was more popular than Daley, who looked exactly the image of a corrupt machine boss. Complicating the primary further was the entrance of Daley’s future arch-nemesis, Benjamin Adamowski, into the primary on a anti-machine platform. Adamowski hoped Kennelly would drop out of the race, and that his reform credentials, combined with the Polish vote, would put him over.

But Daley had the machine on his side. When the candidates applied for the ballot, Daley showed exactly the kind of dirty tricks the machine afforded him. In Chicago, candidates are listed on the ballot in the order they apply. Since voters often pulled the lever on the first recognizable name, having top billing was a coveted position in Chicago elections. Kennelly arrived early, hoping to be first when the city clerk’s office opened at 8:30 a.m. However, Daley’s man entered through a side door early and got his petition stamped first. Daley would be first on the ballot.

Daley may not have had the business establishment backing him, but he had his source of campaign funds. Patronage workers were required to kick back 2% of their salary back to the ward organization, and attend $25-a-plate fundraisers. In addition, contractors who did business with the city and county kicked back money to the machine, knowing that Daley losing would mean the end of their contracts. Organized crime also backed the machine: an anonymous man appeared on TV to say that 10% of the city’s gambling revenue went to politicians. Come election day, there would be plenty of “walk-around” money.

Daley spent very little time directly appealing to voters or taking stands on important issues. Instead, he practiced good old-fashioned machine politics. Daley spent most of his time firing up his precinct captains, trusting them to deliver the votes on election day. He made sure to develop a relationship with as many of them as possible, talking with the men about the White Sox, and the women about their children. The precinct workers in turn, devoted themselves to Daley, knowing their jobs were on the line. Kennelly, in contrast, thought politics was about taking the right stands on the issues. If voters were simply told about his principles, they would naturally support him. “Television is our precinct captain” was Kennelly’s motto, which Daley dismissed. “Can you ask your television set for a favor?” he said.

Kennelly also tried to make the campaign about bossism and corruption. Daley, in response, promised to resign his position as chairman if elected and responded with a theme he would use throughout his career: populism. He insisted the divisions were not between the machine and reformers but between business elites and working class people. “What we must do is have a city not for State Street, not for LaSalle Street, but a city for all Chicago,” Daley told his backers, and defended the party proudly:

“The party permits ordinary people to get ahead. Without the party, I couldn’t be mayor. The rich guys can get elected on their money, but somebody like me, an ordinary person, needs the party. Without the party, only the rich would be elected to office.”

On race, Daley played both sides. He cultivated Dawson as an ally, and made sure to defend him in front of black audiences. Kennelly attacked Dawson, calling him a political boss: “I can understand why Dawson passed the word that he couldn’t stand for Kennelly. I haven’t been interested in building up his power. Without power to dispense privilege, protection and patronage to preferred people, bossism has no stock in trade.” Daley, at the same time, made sure to insinuate upon white audiences that he did not support integration, though he made every effort to dodge a direct question about the issue.

As the primary approached, it seemed that Kennelly had an insurmountable lead: polling indicated the population preferred him 2:1. These of course, were not reliable voters. Kennelly figured that the machine could turn out 400,000 votes in the primary, so if turnout was more than 900,000, he would comfortably win. In the end, turnout was only 750,000 and Daley carried the day with 49% of the vote. Adamowski had split the anti-machine vote as well. When looking at the ward totals however, it became clear how the machine had delivered Daley’s victory. In most wards, Kennelly and Daley ran neck-and-neck, but in the “Automatic Eleven” wards, the machine’s base, Daley had won by Assad-level margins.

While Daley had won the primary, he had not won the mayorship yet. The Republicans had decided to nominate a reform Democrat, Robert Merriam, to run for them, and he promised to be a challenging opponent. Merriam represented the liberal 5th ward and had made a name for himself as a crime fighter by broadcasting actual cases of corruption and crime on his TV show, Spotlight on Chicago. Many Republicans were not enthusiastic about nominating a Democrat as their candidate. The leading national conservative paper, the Chicago Tribune called him a RINO. But Republican Governor William Stratton wanted to breathe life into the Chicago Republican Party, and a fusion ticket between independent Democrats and Republicans was the best promise of that.

The issues ended up being a repeat of the primary, with Daley sticking to platitudes, promising to hire more policemen and to do more for the neighborhoods, though he was vague about exactly what he would do. Merriam attacked Daley for his ties to the machine and promised to continue the civil service reforms Kennelly had started. Daley hit back, mocking Merriam for not being a loyal member of either party. Daley, once again, adopted a populist tone, making the campaign between blue-collar workers and blue-bloods on the lakefront. Merriam, he said, was not a man of the people, unlike Daley, who continued to live in a Bridgeport bungalow with his seven children. Daley promised to put union members on city boards in transit, schools, parks, and health and racked up plenty of union endorsements.

How to Win an Election, Chicago Style

Merriam was concerned that Daley would try to steal the election, or at the very least, inflate his vote totals. This was completely justified. The machine had a number of tactics to steal votes. It began on registration day. Not only would precinct captains make every effort to register voters in their neighborhoods (preferably as Democrats), they would go to flophouses, scan the guest list, and register everyone on it. Since they were transients unlikely to vote, the precinct captains could safely vote for them. The Chicago Tribune, in a 1972 exposé, would create fake voters in the guest lists and watch precinct captains put guests such as “James Joyce” or “Elmer Fudd” on the voter rolls. In addition to flophouse voters, there were ghost voters. Merriam sent 30,000 letters to registered voters in machine strongholds. 3,000 came back as unclaimed, moved, or dead. Merriam claimed that the machine may have as many as 100,000 ghost voters on the voter rolls. The Tribune would later confirm that the machine was indeed voting for ghost voters. Merriam also sent a spy into a west side polling place and caught on camera “Short Pencil” Louie erasing Kennelly votes and replacing them with Daley votes.

The machine had other tactics, such as “four-legged voting,” where the precinct captain would go into the booth with the voter and ensure they pulled the lever for the Democratic ticket. While it served well to ensure voters with a poor command of English voted correctly, it also ensured voters who had been bribed with cash or alcohol kept up their end of the bargain. And when regular voters weren’t available, the machine simply stuffed the ballot box, with precinct captains and election judges alike pulling the lever multiple times. Later investigations would show that there were more votes in some precincts than voters who requested ballots.

According to state law, Republican and Democratic election judges were supposed to be at all polling places to blow the whistle on these sort of tactics. However, the machine had its way of co-opting them. Often ward bosses selected both the Democratic and Republican judges, who were often machine workers who had switched parties. When legitimate Republicans tried to register, the city mysteriously “lost” their applications. If a real Republican did somehow become a judge, they were intimidated into silence. Gangsters would arrive and threaten them if they didn’t leave the polling site. Another judge was arrested when he asked to see the voting records, and released at the end of the day without charges. Another had their dog poisoned. If, on the other hand they looked the other way, they would be treated to breakfast, lunch, and dinner by the precinct captain, along with something extra beyond the $25 they nominally received for judging.

Beyond cheating, the machine had other tactics to convince voters to vote the way they wanted. Before the primary, voters in the Automatic Eleven received a dollar bill in the mail, accompanied by the message, “This is your lucky day. Stay lucky with Daley.”. Voters in public housing and on welfare were told that they would lose their benefits if they didn’t vote for the machine. The machine would appeal to racial prejudices by circulating a fake letter in white neighborhoods saying Merriam’s wife was black (she was not). In Catholic neighborhoods, campaigners never tired of reminding voters that Merriam was divorced and raising two children that were not his own.

Like the primary, Merriam staked his victory on voter turnout. The machine was thought to control 600,000 votes in the general election, and so Merriam needed 1.2 million votes to overcome Daley’s lead. Daley won 708,000 votes on a turnout of 1.3 million, 55% of the vote. Again, the Automatic Eleven had proved critical, especially the African-American wards. In the 1st ward, dominated by the Chicago Outfit, Daley won by 90%. Daley was now mayor, and he would rule the city with an iron fist for the rest of his life.