Mayor: The Life and Times of Richard J. Daley of Chicago - Part II

This is Part 2 of a three-part series on Richard J. Daley

Part 1: Boss

Part III: American Pharaoh

Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. By Mike Royko. 216 Pages.

American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley - His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. By Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor. 624 Pages.

The Man on Five

Daley gave indications of how he would truly govern at his inauguration. During his inauguration speech, he said he would “relieve the council of administrative and technical duties … and permit the aldermen to devote most of their time to legislation.”. His intention was to turn the City Council into a rubber-stamping body for his policies. Daley also went back on his promise to resign his position as Chairman of the Central Committee, pretending he had never made that promise in the first place. Daley realized that if he could push Kennelly out, another chairman could do that to him. In addition, holding the chairmanship allowed him to control slating decisions, which made the aldermen dependent on him for their political careers. They quickly acquiesced to Daley’s “reforms” to the city council, even when he took away their powers to grant driveway permits and zoning variances in their wards, a significant source of bribes. From now on, all favors would be granted from the fifth floor of city hall.

The city council became little more than a cheering section for Daley. No session was complete without an alderman leaping to their feet and declaring, “God bless our mayor, the greatest mayor in the world.“. The few independent aldermen who dared to criticize Daley had their microphones cut off by Daley’s floor leader, Alderman Thomas Keane. Keane and Daley made a great team because where Daley pursued power at all costs, Keane pursued wealth. Daley’s floor leader was all too happy to make sure the city’s business was done efficiently:

On the day a reporter observed him, Keane took up the first item of business, telling the committee secretary that two of the other aldermen on the committee seconded it, though neither had spoken. Keane then declared the motion carried. He did the same thing with six more pending matters, although in each case he was the only one to speak. “Then he put 107 items into one bundle for passage, and 172 more into another for rejection, again without a voice other than his own having been heard,” the reporter noted. “Having disposed of this mountain of details in exactly ten minutes, Ald. Keane walked out.”

Daley’s mentor, Jacob Arvey, gave this advice: “put people under your obligation”. Daley was uncomfortable dealing with people who didn’t owe him anything, and did everything he could to put people under his control. His first move was to undo Kennelly’s reforms to the civil service. It was estimated that each patronage position would yield 10 votes directly or indirectly, and if the city had 40,000 patronage positions, that was 400,000 votes the machine had as a head start against its opponents. Beyond the power that patronage provided, Daley simply thought the patronage system was the way the world ought to work. A patronage job was a reward for hard work, loyalty to the hierarchy, and delivering on election day.

Daley also pursued some good-government initiatives, such as improving city services. Some of Daley’s initiatives were state-of-the-art, such as city-sponsored alcoholism treatment and water fluoridation. But what truly excited him were little things, like filling potholes, street sweeping, and garbage collection. He vowed to install lighting in all of Chicago’s 2,300 alleys. Good government happened to be good politics in this case; hiring more workers to clean the city also gave the machine more patronage. There was a dark side to these improvements: most of it was directed towards the Loop and a few favored wards. And millions of dollars were wasted on workers who did not do their jobs.

Daley, of course, needed money to fund these initiatives. He wanted to increase the sales tax, but that required a referendum. Even with machine control of the election apparatus, such a move was risky: voters are loathe to raise their own taxes. Daley decided to do an end run around the referendum law and appealed to Springfield to allow him to raise the sales tax. He struck a deal with Republican Governor William Stratton, where both the city and state raised the sales tax by a half-cent. Later, rumors would flow that Daley promised to run a weak candidate against Stratton in 1956, which were denied by both men.

The city needed better services, because it was in serious decline. The city’s population would reach a high water mark of 3.6 million in 1950. Over the rest of the century, the city would steadily lose inhabitants to the Cook County suburbs. The Loop especially had seen better days. Where New York had added 10.7 million square feet of office space in eight years, Chicago had built less than one million. The great downtown stores were being abandoned for shopping centers in the suburbs, and the Loop was generally thought of as drab and dirty.

However, the Loop had a powerful ally: Chicago’s business establishment. Fifty-four of the Fortune 500 were based in the Chicago area, most of which were headquartered on State Street. Their fear was that the South Side Black Belt would push north and engulf the Central Business District. Public housing projects, such as Cabrini-Green were located nearby. They turned to a tool provided by the federal government: urban renewal. Their goal was to bulldoze the encroaching slums and build wealthier, whiter housing. Daley, sensing an opportunity to ally with the Republican business establishment, embraced urban renewal.

Another interest group that Daley embraced was organized crime. In June 1956, he disbanded Chicago’s elite gangster unit, known as “Scotland Yard.” A favorite of Mayor Kennelly’s, the unit had spent years bugging and infiltrating the Chicago Outfit. Daley gave no reason as to why he closed down the unit. Soon after, bookie joints and prostitution rings appeared in the Loop again. The police also ignored Outfit violence as they bombed and murdered their way to control gambling in black neighborhoods. Daley always lept to the defense of 1st Ward Alderman/Ward Committeeman John D’Arco, even though D’Arco himself has never bothered to deny that he is the political representative of the Outfit. Daley on organized crime:

“Well, it’s there, and you know you can’t get rid of it, so you have to live with it,” Daley said. “But never let it become so strong that it dominates you.”

A Brief History of Chicago Public Housing

After election, Daley quickly emerged as a leading advocate for the nation’s cities, because he was always on the lookout for more money to develop the city. He eagerly scooped up any funds for public housing, intending to build as many units as the federal government would allow him. In addition to continuing his predecessor’s public housing projects, he proposed two projects of his own: the Clarence Darrow Homes and Robert Taylor Homes. Robert Taylor would be the largest public housing project in the world, with 4,415 apartments spread over 18 identical 16-story buildings. He also began an effort to push out leaders of the Chicago Housing Authority (CHA) and install his own people.

Federal housing programs began as far back as 1933, but took off with the passage of the United States Housing Act of 1937. The need for better housing was dire, especially in Chicago. After the Great Chicago Fire of 1871, which destroyed one-third of the city and left 100,000 homeless, the city permitted the emergency construction of temporary wooden structures. But the emergency never ended, and these temporary structures became permanent well into the Depression. The Depression made the situation worse, as displaced farmers and African-Americans migrated to the city in search of work. Hoovervilles sprung up all over the city, and eviction riots became common. FDR directed that Chicago would get three of the first fifty-one housing projects established by the Act.

Mayor Kelly installed a housing activist, Elizabeth Wood, to lead the newly established Chicago Housing Authority. Wood was an unusual choice. In addition to being a woman, she was far more educated than the rough men who ran the city. But the biggest difference was her idealism: She promised to run a clean agency, with no patronage hires, and to support racial integration.

Achieving racial integration with federal public housing would be difficult. In order to satisfy Southern legislators, the law did not require that housing be integrated. Secretary of the Interior, Harold Ickes, developed the “Neighborhood Composition Rule” for public housing: the racial mix of tenants on a public housing site must match that of the original site. By maintaining the status quo, the rule appeared to sidestep the issue of race. But in practice, it put the local housing authorities explicitly in charge of monitoring the race of all tenants, and was difficult to implement in practice. While white public housing in all-white neighborhoods was not controversial, mixed-race housing in changing neighborhoods was another story. Whites often refused to move in to a project with even a few token black families, and there was intense demand for housing among African-Americans. The Ida B. Wells homes, for example, received 10 applications for every apartment in it. Even all-black housing in all-black neighborhoods was fraught with controversy: nearby whites sued to shift the Ida B. Wells project deeper into the ghetto. When that failed, homeowners added restrictive covenants to their deeds to prevent African-Americans from moving into their neighborhoods.

The end of World War II further strained Chicago’s housing supply. As veterans streamed into Chicago, the nation wanted to do more for these returning heroes. Mayor Kelly directed that public housing be accelerated by building exclusively on land already owned by the city. However, this land was mostly in outlying white neighborhoods, putting the CHA in a bind: federal law required that 20% of the housing go to African-Americans, but the Neighborhood Composition Rule required that the housing projects be entirely white. The CHA decided to abandon the Neighborhood Composition Rule. Whites reacted to the prospect of black neighbors with outright hostility. Wood attempted to compromise, promising that the black families would only have men who were war veterans and women known to be good housekeepers. But before the stricter background checks could be completed, white families helped themselves to the apartments and began squatting in them. The CHA, unable to evict all of the squatters without instigating a riot, compromised again: only families ineligible for public housing would be evicted. Wood was determined to integrate the housing projects, however, and attempted to test the waters by moving two black families to the Airport Homes near Midway. She attempted to move them in at noon, while the men were at work, but the neighborhood women were not having it. They rioted, throwing rocks and attacking the moving trucks, forcing the families and their movers to retreat. It took four hundred policemen to restore order.

The city council, tired of Wood’s idealism, passed an ordinance requiring the council to approve all future CHA sites. They also began looking for ways to undermine her, enraged by her refusal to fill the CHA with patronage positions. Their chance came as her backer, Mayor Kelly left office and was replaced by Mayor Kennelly. While a civil service reformer, he was not a fan of Wood’s integrationist policies, and schemed to replace her. Kennelly pushed the CHA board to hire a consulting firm to examine their operations. The consultants did not talk to Wood, and proposed that a new position of executive director be created, which was filled by Willam Kean. He would run the CHA from now on. Wood went to the press, criticizing the decision, and the board fired her. Daley, while not mayor yet, was likely behind the move: Wood had refused to to hire his cousin as general counsel.

There was a side effect to firing Wood and abandoning managed integration: the city’s public housing quickly became all-black. Whites refused to move into new public housing, and fled the existing ones. By 1969, 99% of all families housed by the CHA were black. Part of this was Daley’s doing; almost all of the housing built during Daley’s tenure was along the “State Street Corridor”, the densest concentration of public housing in the nation. A strip of land one quarter mile wide and 4 miles long, it housed 40,000 poor black residents, and contained almost no other amenities. To further separate the ghetto from the rest of the city, Daley announced the Dan Ryan Expressway, a fourteen-lane superhighway that followed Wentworth avenue, the traditional dividing line between black and white Chicago. The only way Daley could have further separated the neighborhoods was to build a physical wall.

The Robert Taylor homes were a disaster almost from the start. The intention of the homes had been to house the largest families in 3-4 bedroom apartments, mostly headed by single mothers. 20,000 of the 27,000 residents of the project were under twenty-one. Very little thought had been given to the consequences of housing a large number of human beings in the same place with no other institutions nearby. There was a sense the State Street Corridor was a “welfare penitentiary”, with few jobs or diversions for the residents. Sociologists who later studied the area would find that very few residents had ever visited the nearby Loop, and many had never left their neighborhood at all. Unlike Wood’s CHA, the Daley CHA did not screen tenants, and the towers mixed regular families with the criminal element. Assaults on the stairways were so common, welfare workers were told not to use them. Young people passed the time drinking and shooting off guns. Garbage, including televisions, were routinely thrown out the windows, so that maintenance workers wore hard hats.

Daley would later say that nobody could know the consequences of warehousing poor people in a mega-ghetto, but he was in fact warned. Many civic organizations had sent letters urging him to build mixed-income low-rises instead. When confronted with this evidence, Daley changed tack: he blamed the federal government. Federal housing law capped spending at $17,500 per unit, and the CHA estimated that low-rises would cost $22,000 per unit. Daley ignored that private industry was building the same-sized low-rise apartments for $12,900 each. While federal housing law required higher standards than these apartments, some of the costs were due to graft. Robert Taylor cost 22% more than comparable construction in New York. Daley’s insistence on segregation increased the cost further since the crowded black belt neighborhoods had to be cleared before building the high-rises.

But to Daley, the point wasn’t to build quality housing for Chicago residents; it was to control the demographics of the city. Building integrated low-rises was bad politics. First of all, it would spread out the black vote where it wasn’t under the watchful eye of Congressman Dawson. Second of all, white residents would decamp to the suburbs, further diluting the machine’s power. High rises, in contrast, were a precinct captain’s dream. One could simply go from apartment to apartment to round up votes, rather than walking from house to house.

Try as Daley might, he could not keep African-Americans inside Dawson’s three wards forever. They began moving to the West Side, and in 1957 Chicago was swept by new rounds of racial violence. This time, the fault lines were city parks and recreation facilities that were formerly used by whites only. In one instance, over six thousand whites attacked a hundred black picnickers. The riots lasted two days and required five hundred policemen to restore order. The local NAACP chapter became more assertive, criticizing Dawson as a race traitor for remaining silent when his constituent, Emmett Till, was murdered. Dawson plotted his revenge and had his precinct captains sign up en masse for the NAACP chapter a day before the leadership election. He then took over the leadership and ensured they would not embarrass the machine by calling for integration again.

Dawson had been one of Daley’s most loyal followers, backing him against the Kelly-Nash faction, and was instrumental in removing Kennelly. Most importantly, he gave Daley cover on race by opposing integration. But Daley was wary of his power. Unlike most ward committeemen, Dawson controlled multiple wards and a large voting bloc. The growing black population spreading into other wards could increase Dawson’s submachine to four or five wards. Daley decided to move against him. Several wards were referred to as “plantation wards”: majority black, but controlled by white ward bosses. As their white leaders died or moved up the ladder, traditionally slating decisions were given to Dawson. Daley instead started choosing his own men. When Dawson demanded an insubordinate alderman be stripped of his patronage, Daley refused. Dawson raged, but what could he do? His subordinates, sensing the shifting political winds, allied with city hall. However, Daley continued to let Dawson nominally be the leader of the submachine, control the 2nd Ward, and retain his congressional seat. But nobody would be allowed to threaten him, not even his allies.

Redevelopment

In August 1958, Daley unveiled his plan to redevelop the Loop. In the tradition of Burnham’s 1909 plan to redevelop Chicago (the origin of the grid system and standardized lot sizes), it was epic in scale, including an enormous scale model and calling for $1.5 bn ($16.3 bn in 2024 dollars) in investment. Blocks of new government buildings, a new college campus, and housing for 50,000 families were proposed. While writers and urbanists such as Jane Jacobs advocated for pedestrian traffic as the lifeblood of cities, Daley’s plan focused on the automobile. Four new expressways, including the aforementioned Dan Ryan, would radiate from the loop, bringing in customers from the western suburbs. Massive parking garages would be constructed to house their vehicles.

Creating a University of Illinois, Chicago campus had been a dream of Daley’s since his time in Springfield. The problem was that Daley did not have a site to build it on. Daley originally proposed condemning railroad tracks south of the loop, but those tracks were in use, and it was not clear the railroads wanted to give them up. Daley proposed that five railroad terminuses be consolidated into a single Union Station in the Loop, which would free up more than enough land for a college campus. However, the railroads were reluctant to pay for the costs of consolidation. Alternative sites were proposed in the suburbs, but that required the Cook County Board to approve it, and Daley controlled the board. The proposal was defeated unanimously.

Required to build the campus in Chicago, a few sites were considered. One was in Garfield Park. One advantage was that Garfield Park residents wanted a campus. The population of Garfield Park was primarily working class whites, exactly the population the new campus was meant to serve. The neighborhood had fallen on hard times, and residents hoped the new university would give them an economic boost. But Daley and the Chicago business establishment wanted a site closer to the Loop, mostly to serve as a buffer between them and the black neighborhoods. While the University of Illinois trustees had selected the Garfield Park site, but there was a catch: the land was partially owned by the Chicago Park District. Business interests sued, saying that the land had been deeded to the Parks District on the condition it remain a park.

Since the railroads demanded far more money than Daley was willing to pay, he settled on a new site, in what was known as “The Valley”. Originally an Italian neighborhood, the neighborhood now had a mix of Italians, Greeks, African-Americans, and Mexicans. The site was also home to Jane Addams Hull House, which would be closed down or relocated. Where Garfield Park residents saw the campus as a lifeline, The Valley residents saw it as a bulldozer. Quietly, Daley began working to get the archdiocese on his side, and the 1st Ward Organization was given its marching orders. The residents, betrayed by their political leaders, embraced direct action. They turned to housewife Florence Scala to lead them, who led protests to spare their neighborhood. After the city council approved the site for the new campus, they led a sit-in at Daley’s office in City Hall. Daley, uninterested in confronting a group of mothers trying to save their homes, left through a side door. The protestors refused to leave until given an audience with Daley the next day. Daley, when talking to the protestors, blamed the university trustees for the site selection, though he had spent years blocking other sites from going through. 14,000 residents left, destroying one of Chicago’s few integrated neighborhoods.

The following day, Daley announced that the families who lived in the area where the first construction was to occur would have to move out immediately, before their appeals were exhausted. The other residents could remain through the appeal process. The impact of the evictions on neighborhood residents was devastating. “I walked around with Florence Scala at the time when they were clearing people out,” says one reporter. “A lot of the people had lived in that neighborhood their whole lives, the old Italian people. A lot of them died — they just couldn’t make the move.”

Another Daley development priority was a new airport, which had been stalled for years. In 1946, the military donated 1,000 acres and a small hangar to the city, but it wasn’t clear how to fund the construction. La Guardia in New York was losing $1 million ($16 million 2024 dollars) a year, and Chicago’s municipal airport was a similar money-loser. Fees were proposed, but a consortium formed by the airlines threatened to not use the airport if the fees were any higher than at Chicago Municipal Airport (now Midway). Daley bypassed the consortium and negotiated with each airline individually, convincing them to pay the higher fees. Construction began, and an airshow was hosted at an O’hare expanded to 6,393 acres in October 1955.

However, there were some problems: while the city owned the land, it was outside Chicago corporate limits. This meant that Chicago could not police its own airport. Daley wanted to annex a small strip of land to connect the airport to the city, but the suburbs had their own annexation plans as well. In a meeting with the suburbs, Daley promised to not annex any additional land if they agreed to allow the city to annex the airport. Daley almost immediately went back on his word, annexing the land he had promised to the suburbs. Another problem was ground transportation: there was no highway connecting O’Hare to downtown. Commentators referred to O’Hare as “the only airport in the world accessible only by air.” Daley wanted a combined mass transit/highway to whisk travelers to Chicago, but the Kennedy Expressway had been converted to a toll road by a cash-strapped county. State law barred toll roads from including mass transit, and Daley objected to charging visitors a toll to use the airport. Fortunately, the federal government picked up the tab through the Interstate system.

Daley had brought a critical piece of infrastructure to Chicago, and it remains one of the largest airports in the world to this day. However, it was not immune to the usual machine games. The $120 million ($1.4bn 2024 dollars) bond critical to financing the airport’s construction was awarded to a syndicate of five politically connected banks through “negotiation” rather than a competitive bidding process. Critics would also charge that Daley’s second in command, Alderman Tom Keane, was reaping profits from the airport concessions: businesses that retained his law firm got contracts while competitors’ lower bids were ignored. When Keane-connected construction firm Malan Construction was faced with $1 million ($11.62 million in 2024 dollars) in penalties for missing deadlines, Daley waived the penalties.

With these development plans, Daley got the endorsement of the Chicago business establishment, who formed a non-partisan committee to re-elect the mayor. He walked to victory in the 1959 mayoral election with 70% of the vote. While Daley had gotten the endorsement of downtown, he had forgotten his promises to do more for the neighborhoods. Many neighborhoods were spiraling downward on the South and West Sides. As African-Americans moved into these neighborhoods, “panic peddlers” came in, warning whites of an impending black invasion. They were convinced to sell at below-market prices before property prices fell further. The panic peddlers then re-sold these houses to African-Americans at inflated prices, making a tidy profit. Employers moved out of these neighborhoods as well, depriving African-Americans of the good jobs that had attracted them to the neighborhood in the first place. The properties that were sold to landlords were carved up into smaller units, leading to overcrowding. Landlords also stopped maintaining their properties. A study of Chicago housing found that while whites and blacks paid the same median rent, the apartments blacks lived in were significantly smaller and more dilapidated.

Summerdale

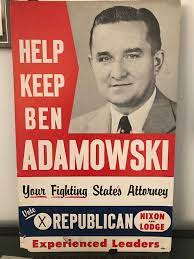

Despite his re-election, there was a thorn in Daley’s side: Benjamin Adamowski. Formerly a Democrat, he had been vised from the machine as punishment for running against Daley in the 1954 primary. Adamowski responded by switching parties and running for State’s Attorney. He won, and dedicated his time to investigating Daley and the machine. The first scandal he uncovered was a ticket-fixing scandal in municipal traffic court. It was no secret that the court had been fixing parking tickets, but the extent of it was surprising. Some employees did nothing but fix tickets. The machine even had dedicated employees to fix reporters’ parking tickets. Daley denied all knowledge of what was going on, but ticket fixing was a mainstay of the machine, and it was impossible Daley didn’t know what was going on. Daley’s response was to create a new office, the Commissioner of Investigation. The office would secretly investigate scandals and report its findings to - and only to - the mayor. It allowed Daley to say he was taking the charges seriously with no risk anything would come of them.

However, the traffic fixing scandal was minor compared to the Summerdale scandal. In 1960, a burglar looking to avoid jail time told investigators that he was assisted by twelve police officers in the Summerdale district for two years. When investigators raided the policemen’s homes, they found truckloads of stolen merchandise. While the robbery ring itself was embarrassing, the real danger was that it would reveal how politics had influenced the police department. That the cops were corrupt was no surprise. Chicagoans were used to paying off the police to avoid a ticket, and the cops routinely collected protection money from bookie joints, gay bars, and prostitution rings. But even Chicagoans were outraged that the police were actively stealing from appliance stores.

Daley immediately fired police chief Tim O’Connor, but he couldn’t appoint someone from the police department to take his place; they were all tainted. Daley needed a reformer in charge of the police, and he selected Orlando W. Wilson, dean of criminology at the University of California. Wilson turned out to be a brilliant choice, since he was an academic and former police officer unconnected to the machine. Wilson, knowing about politician-police relationships in Chicago demanded total independence from City Hall, a three year contract and a salary double that paid by the university. Daley agreed, even though losing patronage in the police department was a painful tradeoff. Incredibly, Daley took the credit for fixing the police department but avoided the blame for looking the other way for five years.

Wilson went to work reforming the police department. Honest cops who were sidelined for years were suddenly promoted, and patronage officers quit rather than face a career of honest work. Police districts stopped following ward boundaries so that ward bosses could no longer directly approve who patrolled their district. Legitimate civil service exams were held, and Daley promised as much money as needed to pay salaries and modernize the force.

The 1960 Election

Despite the scandals, 1960 was shaping up to be a strong year for the Democrats. In 1958, the Democrats made gains in the House and Senate, and the popular Eisenhower would be wrapping up his last term. Daley was looking for a presidential candidate who would help the Chicago slate, and most importantly, recapture the state’s attorney office from foe Benjamin Adamowski. Kennedy, with his Irish-Catholic background, looked like Daley’s best chance of sweeping the ticket into office. Daley was less enthusiastic about Lyndon Johnson, the white southerner, who might turn off black voters. Daley tried to convince Kennedy to nominate another Vice President, reminding him of all he had done to deliver the Illinois delegation, but was coolly rebuffed: “Not you nor anybody else nominated us. We did it ourselves.” Kennedy reportedly told Daley.

The State’s Attorney race was shaping up to be an ugly fight. Daley, rather than picking a machine hack, slated reformer Daniel Ward. Adamowski insisted his campaign was not against Ward, but Daley and the machine - Ward was just his patsy. Adamowski continued to dig up more scandals involving the machine. He found that city employees were taking bribes to help a trucking company short-weight construction supplies for the city. Another scandal was a new one; judges were ordering that bondsmen have their money returned even when Outfit figures jumped bail. Adamowski’s investigations ensured that negative headlines were constantly in the press, and Adamowski himself was constantly attacking Daley. Daley, in turn, called Adamowski a “sadly inadequate person” trying to “soft-pedal and cover up his own failures.”

As November approached, allegations surfaced that Daley was preparing to steal the election. Almost all of the jobs at the Board of Election Commissioners were held by machine Democrats. Gangsters were threatening homeowners who put up Adamowski signs, and city workers were tearing down Republican signs from telephone poles. While signs were prohibited from telephone poles, the Democratic signs were left alone. More seriously, the Chicago Daily News uncovered thousands of ineligible voters on the voter rolls.

November 8 came, and after voting, Daley holed up in his office to await the results. Turnout was incredible in Chicago: 89% of eligible voters were estimated to have voted, compared to a national turnout of 64%. It was clear that the election for president would come down to the wire. Republicans began to fear that the machine would repeat an old tactic: wait until downstate results came in, and then report vote totals just above what was needed to win. Daley charged that downstate Republicans were doing the same thing. Suspiciously, results came in for all races except the state’s attorney race.

When the tally was completed that night for the presidential race, nowhere was the result closer than Illinois, where Kennedy won the state by only 8,858 votes out of 4.6 million cast. Key to Kennedy’s victory was Chicago, where he held a lead of 450,000. The Automatic Eleven had delivered 170,000 of those votes, more than Daley had squeezed out of them in his mayoral election. The Republicans suspected a fix was in and demanded a recount. Daley obliged, but counted one precinct per day. At that pace, it would take 20 years to complete the recount. Nixon gained very little in the initial precincts canvassed, but Adamowski switched at least 7,000 votes. Since there was nothing to gain for Nixon, the RNC gave up and left the cost of the recount to Adamowski. Adamowski, unable to afford a recount, conceded the election to Ward.

Was the election of 1960 stolen? Illinois by itself would not have swung the election. But combined with Texas, with another small margin of victory, it could have swung the election to Nixon. Lyndon Johnson was not above cheating in an election either. Did Daley steal Illinois to win the state’s attorney race? It’s possible, and there’s some testimony that corroborates this:

Andre Foster recalls sitting in his father’s polling place in a barbershop on Roosevelt Road that night when someone came to the door after the polls had closed. “Some guy knocked on the door and said, ‘We need thirty more votes,’” recalls Foster. “I heard him say it.”

The errors in the 900 Cook County precincts that used paper ballots showed patterns that consistently favored the Democrats. In some precincts, the errors were incredibly large. In the 57th precinct of the 31st Ward, Tom Keane’s home turf, the tally was 323-78 for Kennedy, but the recount showed 237-162. Ward’s victory plunged by two-thirds in the same precinct. Daley plead innocent, saying similar discrepancies were happening downstate, not just in Chicago.

Grateful for his help getting him elected, Kennedy invited the Daleys to be the first visitors to his White House. Things were looking up for Daley: he had successfully brought billions of dollars of investment to Chicago, at the cost of raising property taxes 86% in his first seven years in office. He would soon have a taxpayer revolt on his hands. In addition, the tumultuous 1960’s were dawning. African-Americans would demand equal rights, something Daley was not prepared to grant.