American Pharaoh: The Life and Times of Richard J. Daley of Chicago - Part III

This is Part 3 of a three-part series on Richard J. Daley

Boss: Richard J. Daley of Chicago. By Mike Royko. 216 Pages.

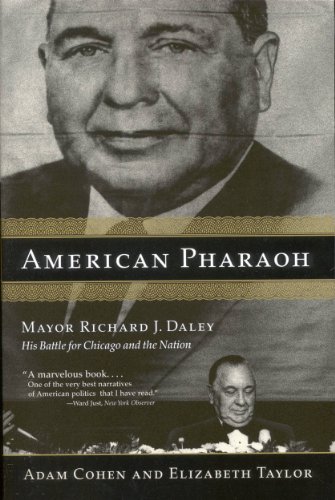

American Pharaoh: Mayor Richard J. Daley - His Battle for Chicago and the Nation. By Adam Cohen and Elizabeth Taylor. 624 Pages.

Education

As the Civil Rights Movement gained steam in the South, black Chicagoans watched with interest. Chicago’s schools were just as segregated as any you would find in Alabama and Mississippi. They were just as unequal as well; the average black Chicago school had twice as many students as white ones. The city had built a few new schools in black neighborhoods, but not nearly enough to accommodate the influx of new residents. School superintendent Benjamin Willis’s solution was to convert the overcrowded schools to double shifts. And yet, many white schools had vacancies, with many classrooms in high schools sitting empty. When parents applied to transfer their children to underutilized white schools, they were instead transferred to distant black schools. Parents began to protest, led by activist Saul Alinsky. “Death watches” were held at the Board of Education meetings, where members held a vigil dressed in black.

During these protests, Daley kept a low profile. He was philosophically against integration and politically the issue was a third rail for him. If he came out for integration, white voters would abandon him. But if he came out against integration, he would lose African-American voters. Instead, Daley tried to dodge the question, saying he was “Avoiding inserting politics into the schools”. Strange words from a man who was elected with the speech: “My opponent says, ‘I took politics out of the schools; I took politics out of this and I took politics out of that.’ I say to you: There’s nothin’ wrong with politics. There’s nothing wrong with good politics. Good politics is good government.”

The protestors formed the Coordinating Council of Community Organizations (CCCO) as an umbrella organization for all the civil rights groups, including the local chapter of the NAACP. They decided as a goal to unseat superintendent Willis, who made an ideal villain. While Willis championed teacher salary increases and small classroom sizes in white schools, he was arrogant and dismissive to black critics. He made no effort to meet the protesters, and took white schools off the list of potential transfers. When the school board got a court order to reinstate the schools, he resigned his position. As a ploy, it worked. White community groups wrote letters to Daley asking him to be reinstated as superintendent. Daley duly reinstated him, to the outrage of the CCCO members. They started working on a school boycott, with thousands of parents promising to keep their kids out of school that day. On October 22, about 225,000 students stayed out of school.

However, the boycott failed to persuade the mayor or Willis to change tack. Instead, CCCO leader Al Raby filed a complaint with the U.S. Office of Education charging the Chicago Board of Education with segregation and requesting the federal government withdraw all funding until the system desegregated. When education was only financed by state and local taxes, such a complaint would not have mattered. But in 1965, President Johnson signed the Elementary and Secondary Education Act, appropriating aid to the nation’s schools. The law was intended to serve as a carrot for southern schools to desegregate; the money would only go to integrated schools. What Daley had not considered is that this requirement would also apply to Chicago Public Schools. The U.S. Commissioner of Education, Francis Keppel, sent a team of investigators to Chicago. Willis, ever intransigent, refused to cooperate with the investigation. Keppel, in response, cut off Chicago’s $32 million in aid ($315 million 2024 dollars).

Daley was infuriated by Keppel’s actions. He went directly to President Johnson, interrupting his meeting with the Pope. Johnson, still planning to run for president in 1968, wanted to keep Daley on his side and restored the funding on the condition that the Chicago Board of Education investigate themselves. Unsurprisingly, they found nothing wrong and dropped the matter quietly. Keppel was demoted to assistant secretary of education and replaced by a man who would not cross Daley. The Johnson administration also resolved not to investigate future complaints of discrimination in Northern cities.

Segregated schools were not the only area where Johnson overlooked Daley’s violation of federal law. One initiative, the Community Action Program (CAP) required that it be “developed, conducted, and administered with the maximum feasible participation of residents of the areas and members of the groups served.”, known as the “maximum feasible participation” rule. Welfare had traditionally been run by downtown bureaucrats, far away from the people it was meant to help. Instead, the CAP was going to be run by neighborhood-based organizations with the input of the poor themselves. Daley was philosophically opposed to welfare but was willing to accept any federal funding being distributed. Politically, though, he was opposed to the maximum feasible participation rule. Distributing money to neighborhood organizations like CCCO would not help the machine or allow Daley to create more patronage. He also feared that the money would be used against him, telling Johnson aide Bill Moyers that the president was funding subversives.

To get around the maximum feasible participation rule, Daley established the Chicago Committee on Urban Opportunity (CCUO) to oversee the War on Poverty programs and named himself chairman. The board members were a list of prominent Democratic fundraisers, and CCUO was staffed with machine loyalists. The federal Office of Economic Opportunity (OEO) saw through this ruse but was overruled by the Johnson administration, who did not want to anger Daley. Predictably, the money ended up not helping the impoverished: 27% of children enrolled in Head Start were above the income limits, including many affluent children. 70% of all anti-poverty funds in the city were spent on the salaries of employees, indicating the money was mostly used for patronage.

The 1963 Election

The early 1960s were boom years for Chicago. Architectural Digest dedicated its May 1962 issue to the new skyscrapers coming up around Chicago. Three million square feet of office space were added, new government buildings were built, and the Loop expanded north and west. Even before Daley announced his 1963 re-election campaign, endorsements came in from businesses and unions alike. When the time came to bring in nomination signatures, Daley filed a sixteen-foot stack of signatures bearing 750,000 names.

However, scandals continued to surface, damaging the machine and Daley’s reputation. The fire department had been caught looting the houses of fire victims, and government reports detailed incredible amounts of wasteful spending by the city government. Days after the aldermanic elections, machine politician Benjamin Lewis had been found dead, tied to a chair, and shot to death. The murder had the hallmarks of a gangland execution, but nobody was ever arrested.

Daley foe Adamowski was selected by the Republicans to run against him for mayor in 1963. Adamowski challenged Daley’s assertions that city services have gotten better and reminded voters that their property taxes had nearly doubled in Daley’s time in office. Republicans in Springfield proposed a bill to cap Chicago’s taxes, which Daley defeated, at the cost of reminding voters that he planned to spend more and tax more while in office. Adamowski came out forcefully against integrated housing in a bid to sweep up white voters and took a populist tone:

“I hear State Street is against me, the bankers are against me, and the labor leaders are against me,” he declared, in remarks that sounded uncannily like Daley’s in 1955. “State Street doesn’t make Chicago big, it’s the other way around. I’ll take Western Avenue, Nagle Avenue, Ashland Avenue, and Milwaukee Avenue, where the little people reside. I’ll take the bank depositors over the bankers any day. That goes for the little people in labor, too.”

Daley’s response was to dodge the integration issue, telling reporters, “You know my record” when asked about it. He attacked Adamowski’s integrity, revealing that during his time as State’s Attorney, $800,000 ($8.1 million 2024 dollars) was unaccounted for in a mysterious discretionary fund. Adamowski replied that the money was used to pay informants, and reminded voters that the “reformed” Daley police had let Summerdale informant Richard Morrison be shot to death while leaving court. Adamowski also found forty-three similar funds in the city government that Daley had not accounted for.

When the votes were tallied on April 2, it was the much closer than the 1959 rout. Turnout was low: Daley fell below 700,000 votes for the first time, and won with only 55.7% of the vote. When the ward totals were tallied, Daley had only won 49% of white voters, and had made up the difference by getting 81% of black voters. Daley had two choices: try to run as a liberal integrationist reformer, cobbling a majority from African-American machine voters and moderate white voters, or double down on segregation and try to win back white machine voters. Daley would choose the latter, with disastrous results for his most loyal voting bloc.

Martin Luther King

In early July, delegates met for the annual NAACP national convention in Chicago. Daley was invited to give a speech, where he incredulously claimed that there were “no ghettos in Chicago.” Dr. Lucien Holman, who headed the statewide chapter, interrupted Daley, “We’ve had enough of this short of foolishness.” Daley then led a procession of 50,000 civil rights marchers through the Loop. Finishing at Grant Park, the parade organizer asked him to make some remarks. As he began, the crowd started to shout, “Daley must go!” and “Down with ghettos!“. Embarrassingly, some city employees joined in the heckling, and after fifteen minutes, Daley left the event. It was a sign of changing race relations in Chicago. Worse for the machine, they were defeated by independent Charles Chew in the 17th Ward aldermanic race. Unlike the “silent six” aldermen who followed Daley’s lead on civil rights, Ald. Chew was free to defy Daley on open housing.

Martin Luther King, after winning breakthrough victories in the South in 1965, was considering the next move of the SCLC. On one hand, work still needed to be done to register voters and ensure the civil rights acts congress had passed were enforced. On the other hand, Northern cities had gotten a pass on segregation and poverty. Such a shift would require a new strategy. While the South had used the law and government to enforce segregation, Northern laws were at first glance race-neutral. Discrimination was informal and private, such as realtors steering customers towards specific neighborhoods or racial preferences in union apprenticeship programs. Martin Luther King made his choice to come to Chicago after the Watts riots in Los Angeles. Kong was struck by the poverty in Watts, and concluded he had mistakenly concentrated only on the condition of blacks in the South One reason he focused on Chicago was not only because it was the most segregated city, but because of Daley. King reasoned that if he could convince Daley that he was right, Daley was so powerful that he by himself could change the system.

By the fall of 1965, rumors were spreading that King was coming to Chicago. Daley said he would be happy to meet Dr. Martin Luther King: “No one has to march to meet the mayor of Chicago…The door is always open and I’m here 10 to 12 hours a day.” But quietly, he started mobilizing black machine politicians to undermine King’s campaign. He formed his own group, Chicago Conference to Fulfill These Rights, Inc., which insisted that King was not grounded in Chicago enough to be an effective leader. Ald. Ralph Metcalfe declared, “This is no hick town…we have adequate leadership here.”

King announced in January 1966 that he would be moving into a West Side tenement. As a PR and organizing strategy, it was brilliant. King would be sharing the hardships of his fellow citizens. The West Side contained the most recent arrivals from the South, and were not as tied to the machine as South Side African-Americans. The West Side was also significantly worse than the South Side. One tenement King toured was burned out in a fire, and had no heat, hot water or electricity. Other buildings had large holes in the walls, and mothers had to hold nightly candlelight vigils to protect their children from rats. King asked renters if they had considered a rent strike, and made a point of meeting gang members, preaching non-violence to them.

There were challenges King did not expect to face. Black politicians and ministers connected to the machine were actively hostile to King’s campaign. “Chicago was the first city that we ever went to as members of the SCLC staff where the black ministers and black politicians told us to go back where we came from,” said one SCLC employee. And while King wanted to convince Daley to change things, they spoke different languages. King spoke the language of moral right, while Daley only spoke the language of power. To Daley, protests and marches were not legitimate ways of effecting change - who had elected King to anything?

Daley was not a Bull Conner or George Wallace; he knew better than to become a villain in King’s campaign. When King talked about rent strikes, Daley organized one of his own. The county welfare department paid for housing for many poor families, and Daley threatened to withhold that money unless slumlords cleaned up their act. Daley then announced a drive to inspect buildings and fine landlords who were not up to code. Chicago had one of the strictest building codes in the nation, but it was selectively enforced; only landlords who crossed the machine were inspected. “We are all trying to eliminate slums,” said Daley.

King started leading marches into segregated neighborhoods, where he encountered unbridled white hostility. Where they marched, a hostile crowd showed up and pelted them with bottles and rocks. King would later say, “I think the people from Mississippi ought to come to Chicago to learn how to hate.”. Daley wanted the marches to end but understood that using force would only help the protestors. Where white homeowners thought he would help them, he simply said that law and order must prevail and the protestors had a right to march. Daley wanted to negotiate. While he could have easily passed an open housing ordinance himself, he instead convened a housing summit where he was the mediator and the Chicago Freedom Movement was negotiating with the Chicago Real Estate Board.

At the summit, Daley refused to explicitly disagree with King but was also vague about what he would actually do. He called the problem a metropolitan one, noting that the Cook County suburbs were also segregated and closed to public housing. Daley blamed the Republicans in Springfield for not passing a statewide open housing law. Daley did get the Chicago Real Estate Board to promise it would withdraw its opposition to a fair housing bill and adopt a motion to have its members practice non-discrimination. However, King perceived this as an empty gesture, since the statewide Real Estate Board would still oppose the law on behalf of Chicago and there were no sanctions for realtors who discriminated by race. King pressed Daley to be part of the solution and pass a citywide fair housing ordinance. Daley was noncommittal, insisting marches would have to stop first.

Tired of waiting for King to stop marching, Daley turned to the courts. Most of the judges had been appointed on his say-so, and Daley was not shy about telling them how to rule on a case. Daley’s lawyers filed an injunction in Cook County Circuit Court, and a machine judge granted it. While the injunction did not ban all marches, it put significant restrictions on them. Only five hundred marchers could participate; the protests had to be held during daylight but not during rush hours; and the march route had to be submitted to the police twenty-four hours in advance. King was outraged; even George Wallace had not been able to get such an order in the Alabama courts. Some members suggested violating the injunction, but King ruled against it, worrying that breaking the law would cede the moral high ground. Thinking he had bit off more than he could chew in Chicago, he decided to keep negotiating with Daley, hoping for any kind of win.

The two sides eventually settled on ten points. The city would not pass an open housing law, but do more to enforce existing legislation. Daley would work in Springfield to pass a statewide open housing law. The Chicago Housing Authority would build future sites across the city, and limit building heights to eight stories. The Real Estate Board would do more to ensure its realtors did not discriminate. The language was vague and unenforceable, but it was enough for King to declare victory and leave Chicago. However, the compromise satisfied nobody and outraged everyone. White working class residents were convinced Daley had sold them out and allowed their neighborhoods to integrate. Blacks were just as convinced they had been betrayed for empty promises. They were correct; once the 1966 elections were over, Ald. Keane declared there was no agreement, only suggestions, and nothing would be done in the future.

When Martin Luther King was assassinated on April 6, 1968, Daley began to speak of him as a fallen comrade. “Chicago joins in mourning the tragic death of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr.,” Daley said in a prepared statement. “Dr. King was a dedicated and courageous American who commanded the respect of the people of the world.”. While Chicago had escaped most of the rioting of the 1960’s, this time it would not be so fortunate. Looting followed the day after, along with arson and sniper attacks. Daley showed up on television, and gave a bizarre rant blaming the riots on conditions in the schools:

“The conditions of April 5 in the schools were indescribable,” he said. “The beating of girls, the slashing of teachers and the general turmoil and the payoffs and the extortions. We have to face up to this situation with discipline. Principals tell us what’s happening and they are told to forget it.”

The school superintendent said he had no idea what Daley was talking about. Daley dropped the matter, but became more inflammatory:

“I said to him [the Superintendent of Police] very emphatically and very definitely that [he should issue an order] immediately and under his signature to shoot to kill any arsonist or anyone with a Molotov cocktail in his hand in Chicago because they’re potential murderers, and to issue a police order to shoot to maim or cripple any arsonists and looters — arson-ists to kill and looters to maim and detain.” Daley said he had thought these instructions would not even need to be conveyed. “I assumed any superintendent would issue instructions to shoot arson-ists on sight and to maim the looters, but I found out this morning this wasn’t so and therefore gave him specific instructions,”

Many cities were wracked by rioting in the wake of King’s death; Daley was the only leader to order the police to shoot to kill. Daley’s comments triggered outrage and controversy, and he backtracked, blaming the news media. He claimed there was never a shoot-to-kill order, and that the press should have printed what he meant, not what he said.

Once the riots were over, Daley assembled a package of federal and state aid to rebuild the West Side. He did very little to examine the root causes of the riots, not even bothering to note that rioting was concentrated in the much poorer West Side and not the South Side. The West Side consisted mostly of African-Americans who had recently migrated from the South or had been displaced by Daley’s urban renewal programs, and were poorer and less educated than their South Side counterparts. The West Side had less churches and community organizations. This combination of displacement and disappointment made it a tinderbox for civil unrest.

The 1968 Democratic National Convention

Daley’s control over the city was soon challenged by the growing peace movement. As a harbinger of what was to come, the Chicago Peace Council made plans to hold a rally on April 27. They applied for permits from the Chicago Park District, but were stalled, then denied a permit. William McFetridge, president of the Parks District, said that it was the district’s policy to “keep unpatriotic groups and race agitators from using the parks.”. Only the threat of a federal lawsuit gave the group a permit.

About 6,000 protestors marched from Grant Park to Civic Plaza (now Daley Plaza). Five hundred police officers were assigned to watch the protestors, an extraordinarily large force for a small crowd. Less than one hundred officers were typically assigned to sporting events, with 45,000 fans in attendance. The protestors marched on the sidewalk in groups. All witnesses, including the police, agree that there was no violence. Nothing was thrown, no windows were smashed, nobody even heard the word “pig” directed at the police. The police decided the crowd should disperse and ordered them to do so. But other officers were blocking the exits from the plaza. Suddenly, the officers started beating the protestors. After they started making arrests, one officer sprayed an entire can of Mace into the paddy wagon and shut the door. Later, after the convention, this sort of incident would be termed a “police riot.” Because the previous peace marches had been uneventful, the media sent nobody to cover the march, and the riot was ignored.

Daley was hard at work preparing for the 1968 convention. To obscure the blight and slums, Daley built miles of wooden fence between the Loop and the International Amphitheatre. Chicago had labor problems as well. The transit employees, electrical workers, and taxi drivers went on strike days before the convention. Daley had to scramble to negotiate settlements in time for the convention but was unable to resolve the taxi strike. He instead chartered buses to take delegates between hotels and the Amphitheatre. Extensive security preparations were made around the convention site: barbed-wire fence was erected; manholes sealed with tar; and helicopters patrolled for snipers in nearby public housing. Reporters took to calling the International Amphitheatre “Fort Daley”.

The peace groups were making their own preparations as well. They were planning to bus thousands of protestors to confront the Democratic power establishment at the convention. The party of Lyndon Johnson, the instigator of the war, was the logical target of the anti-war movement’s rage. Daley himself was another reason; he was perceived as exactly the authoritarian establishment figure they were fighting against. While Daley had deep misgivings about the Vietnam War, he had never broken with the President on the issue, and remained a steadfast supporter of Johnson.

What the anti-war movement wouldn’t know until years later was that Daley had infiltrated them. The Chicago Department of Investigation, the mayor’s personal intelligence unit, and the Chicago Police Department’s “Red Squad” had over 800 informants in various groups like the National Mobilization Committee to End the War (MOBE) and the League of Women Voters. “As a result of our activities in New York, instead of 200 busloads of demonstrators coming to Chicago, they ended up with eight carloads, totaling 60 people,” wrote one operative. Informants discouraged protestors from coming to Chicago, and tried to set different anti-war groups against each other. One police officer broke into the Chicago Peace Council’s headquarters, stole equipment, and spray painted slogans from Students for a Democratic Society.

“The police have a perfect right to spy on private citizens,” Daley insisted. “How else are they going to detect possible trouble before it happens?”

Protestors started arriving a week before the convention. As with the April 27 protests, city hall dragged its feet on giving permits to MOBE and the Youth International Party, or Yippies. This time, they were forced to sue for the permits, but unfortunately got as their judge Daley’s former law partner William J. Lynch, who denied the protestors permission to march near the convention. MOBE also asked for permission to lift Grant Park’s 11 PM curfew, so that members who could not afford a hotel could sleep in the park. Permission was denied by Lynch as well.

The Yippies were one of the more colorful groups to attend the convention. Leader Abbie Hoffman wanted to make the concept of revolution “fun” and threatened to pull a variety of stunts in Chicago. They talked about sending sexy male yippies to seduce the wives of delegates, adding LSD to the Chicago water supply, and pulling down Hubert Humphrey’s pants at the podium. While these were empty threats, they did create a “festival of life” in Lincoln Park, a be-in of meditations, poetry reading, and political speeches. There, they nominated a pig named Pigasus for president. When they took the pig to the Civic Center for a press conference, the police arrested the pig.

With the national press arriving, Daley wanted to portray himself as a competent city executive. But Daley’s relationship with the media was strained. Television stations were unhappy with the restrictions imposed. Television cameras were not allowed to be placed outside the Amphitheatre, and police refused to allow television vans to park in front of the hotels where delegates were staying. CBS called the ban a “totally unwarranted restriction of free and rapid access to information.” CBS correspondent Eric Sevareid added that Chicago “runs the city of Prague a close second right now as the world’s least attractive tourist attraction.”

Daley would be playing kingmaker as well as host. With his control over the Illinois delegation, he was one of the few wild cards, leaving the nomination in doubt. Going into the convention, it was not clear who he would support. Vice President Hubert Humphrey was the frontrunner, but many delegates were complaining he was a weak candidate. Daley was concerned that he would bring down the machine ticket, but senators Eugene McCarthy and George McGovern were even worse. Daley was hoping to draft another Kennedy into the nomination: Edward Kennedy. Daley played his cards close to his chest, refusing to say who he would endorse. Behind the scenes, however, Daley was trying to convince Kennedy to run.

Meanwhile, the anti-war protests were turning ugly. At 11:00 p.m., the police charged in to enforce the rarely invoked curfew. Shouting “Kill, Kill, Kill”, the police spent the next three hours beating anyone found in the park, including bystanders. Two police told a reporter that “the word is out to get newsmen.”. Daley would later deny that reporters were specifically targeted, but press coverage turned against Daley after reporters were specifically targeted by the police.

The next day of the convention, Kennedy explicitly took himself out of the running despite a groundswell of support for him to run. The party was still bitterly divided over Vietnam and argued until past 1 a.m. if a peace plank should be added to the Democratic platform. The arguments continued until Wednesday, when 5,000 protestors assembled on Michigan Ave. outside the Conrad Hilton Hotel. The police ordered the crowd to disperse, and after getting no response, charged the crowd. What followed became known as the Battle of Michigan Avenue. Police attacked protestors and bystanders alike and even threw people through restaurant windows.

This time, however, the whole world was watching. Television cameras had been set up outside the Hilton, and captured the entire orgy of violence. The networks cut between shots of police beatings and images of Daley laughing at the convention, giving the impression he was celebrating the violence. When word reached the Amphitheatre of what had happened, divisions between the Democrats intensified. Speakers abandoned their prepared remarks, and started criticizing Daley. Connecticut senator Abraham Ribicoff declared that “With George McGovern we wouldn’t have Gestapo tactics on the streets in Chicago.”. Daley flushed and screamed “Fuck you, you Jew motherfucker, go home”.

While the world may have condemned Daley’s actions, Chicago seemed to approve of them. Cars around the city displayed “We Support Mayor Daley and His Chicago Police.” bumper stickers, and Daley’s mail overwhelmingly supported the police’s actions. Reporters criticizing the events got hate mail:

Jack Mabley, a columnist with Chicago’s American, had written one of the most disturbing pieces of reportage to come out of the convention. It described a policeman who “went animal when a crippled man couldn’t get away fast enough.” The policeman, angry that the man hopping along with the help of a stick was not gone, shoved him in the back, hit him with a night stick, and threw him into a lamppost. Mabley got an overwhelming response to his reporting — 80 percent to 85 percent of it supporting Daley and the police. “You can’t help that gnawing feeling — can all these people be right and I be wrong?” Mabley said.

The last day of the convention, Daley packed the gallery with patronage workers, who chanted “We love Daley” as he entered the convention hall. Daley made himself available to be interviewed by Walter Cronkite, where he blamed the protestors and media for the violence. During the interview, Daley claimed that he had evidence that among the protestors were assassins planning to kill the presidential candidates. If there was a plot, Daley seemed to be the only person who knew about it. The FBI did not know what he was talking about, nor did anyone in Daley’s inner circle know about it before he talked about it with Cronkite.

Final Years

The stress of the convention and its aftermath took a toll on Daley’s health. He began falling asleep during events, and was noticeably slower and more withdrawn . Never known for his oration skills, Daley’s speeches became more incoherent and nonsensical. Open to reporters, Daley now hosted less press conferences and denied reporters access to his office. Daley also became more concerned about his physical security - police officers were posted outside his house, a tail car began to follow him, and the mayoral limousine had bulletproof glass installed.

On February 10, 1969, a federal court ruled in the Gautreaux case. In this case, brought by the ACLU against the Chicago Housing Authority, the obvious was confirmed: that the CHA had discriminated against African-Americans for decades. In addition to only building public housing in all-black areas, the CHA maintained separate waiting lists for white and black families. The judge ruled that the CHA must address the illegal discrimination. When it failed to do so, he ordered that 75% of future public housing sites be built in white neighborhoods. Fearing a backlash from white voters, the CHA stalled for two years, appealing the decision until it lost at the Supreme Court. Daley argued that the suburbs needed to be part of the solution, where economic opportunities were better. A pilot program was later tested in the suburbs and produced impressive results. Studies showed that impoverished families that moved to the suburbs had more education and employment success than those who remained in the ghetto. But because it was built at the end of the era of federal public housing, the demonstration program was quickly forgotten.

Daley’s next concern involved the formation of a Black Panthers chapter in Chicago, led by Fred Hampton. The Black Panthers, initially viewed as just another gang, gained credibility when they established a clinic and a free breakfast program. As they became more popular, the FBI and Chicago Police became more intent on squashing them. In the early morning of December 4, 1969, the police raided Fred Hampton’s home with a search warrant for a cache of illegal weapons. Gunfire broke out, and Hampton and fellow Panther Mark Clark were dead. The police claimed the Panthers had started firing at them and were forced to return fire. But the police made the mistake of not sealing off the house, and the Panthers led reporters through the house, noting that the bullet holes were only on the side opposite the police in the building. Further investigation revealed Hampton had been lying in bed when he was killed. While a federal grand jury did not return any indictments and a blue-ribbon panel claimed the incident was justifiable homicide, there were local indictments. State’s attorney Edward Hanrahan and thirteen other officials were indicted with conspiring to obstruct justice in a police cover-up, though none of them were convicted.

The Black Panthers scandal would erode machine support among blacks on the South and West sides, significantly damaging the machine. Politicians who were previously machine loyalists began to break with Daley. Most significant was Congressman Ralph Metcalfe, one of Daley’s “silent six” who could be counted on to vote against integration proposals. In response to the police brutality he had seen, he became one of the machine’s harshest critics. Daley, in revenge, stripped away his patronage but could not take away his congressional seat.

Scandals continued to dog the machine. Nixon appointed U.S. Attorney James Thompson, who made it his priority to investigate big-city Democratic machine corruption. First to fall was former governor Otto Kerner, now a sitting federal judge; he was charged with bribery and tax evasion. He had been bribed while governor by a racetrack owner to add extra horse racing days. In return, he bought stock in the racetrack for far below its value. Then Thompson indicted seventy-five people for vote fraud. In some precincts, the fraudulent votes were 50% of the total cast. Sixty-six people would be found guilty.

Most damaging of all was the Shakman case. In it, a federal appeals court ruled that other than high-level officials, city workers could not be fired for their political affiliation. Without the threat of losing their jobs, patronage workers would not feel the same pressure to deliver on election day. It did not completely dismantle the patronage system, since workers could still be hired based on political affiliation. But later, after Daley’s death, Shakman II would prohibit hiring workers on political grounds and destroy the machine once and for all.

New scandals started to touch Daley personally. In 1973, it was revealed by Chicago Today that shortly after his son John joined the insurance firm Heil & Heil, the city had switched almost $3 million ($21 million 2024 dollars) in city insurance premiums to the firm. Even worse, it would later surface that John and William Daley had actually failed their insurance license tests. Their exams had been altered to give them a passing score. The employee who had altered the tests was fired, but later hired in another patronage position with a pay raise. Daughter Patricia Daley’s house was found not to have been re-appraised after making significant improvements to it. Then came charges came Daley himself was hiding money; the Chicago Sun-Times found that the Daleys had a secret real-estate firm with $200,000 in assets ($1.25 million 2024 dollars).

While some of Daley’s power had been chipped away, he continued to rack up election victories and cruised to victory in the 1975 mayoral election. However, the influence of the machine began to wane. Metcalfe retained his congressional seat, and Daley failed to unseat state’s attorney Bernard Carey. Daley’s health began to deteriorate further, and he died on December 20, 1976 at 74 years old. Daley lied in state at the Nativity of Our Lord Church, where people waited hours to say farewell to their mayor. At the request of the Daelys, there was no formal eulogy, and nothing was mentioned of his accomplishments at the funeral mass. But it was undeniable that he had touched millions of lives during his mayorship.

The Chicago that Daley left behind was one filled with contrasts. The Loop hosted the world’s tallest building and had been subject to much redevelopment over the Daley years. Gleaming skyscrapers and residential buildings rose up over the Loop. On the other hand, many Chicago neighborhoods were left behind by Daley’s policies. The Chicago Daley left behind was segregated and unequal—a city that began the 1960s with one in ten residents on government assistance and ended the decade with one in five. Daley left behind a legacy of segregation, inequality, and corruption. Property taxes had doubled on his watch, mostly to fill patronage workers’ and contractors’ pockets. The population of the city was beginning to decline, and urban blight was spreading. Daley’s methods were crude and corrupt, and seem out of place to us today. But this last of the machine bosses ensured America’s second city would stay that way.

<< Previous