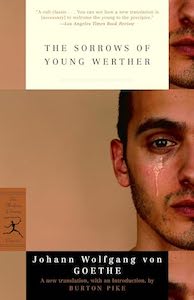

The Sorrows of Young Werther

The Sorrows of Young Werther. By Johann Wolfgang von Goethe. 144 pages.

When I picked it up, I only knew The Sorrows of Young Werther for its reputation as an early Romantic novel that took Europe by storm when published in 1774. I expected a typical romantic novel, full of melodrama and lacking in self-awareness.

It was not the book I expected.

Werther might be a romantic hero, but Goethe makes him an obnoxious, unlikeable one. I’m surprised that so many people wanted to emulate Werther, even if they felt the like he did. What doesn’t surprise me is that Goethe came to dislike the book in his old age; a lot of people missed that Werther is not that admirable.

Synopsis

The book is told in a series of letters written by Werther to his friend Wilhelm. Werther is basically a NEET - he doesn’t want to get a job; he wants to do art. However, at the same time, he tells Wilhelm that he is too happy to do art and society is too stratified for him to authentically express himself. He mooches off various people throughout the novel, living at their homes or drawing money from his mother. He talks about the value of living off the fruit of one’s labor, but has his meals and garden prepared by servants.

Werther moves to the village of Wahlheim, where he is enchanted by the simple ways of peasants. At a ball, he meets Charlotte and is instantly smitten with her. Charlotte’s mother died young, and she takes care of her younger siblings. Werther admires Charlotte’s self-sacrificing nature and they bond over their shared interests in the arts, but she is engaged to the nobleman Albert. Werther does not have the wealth of Albert, only being upper middle class, but tries to pursue a relationship with Charlotte anyways.

Werther, realizing the impossibility of the situation, gets a job as a secretary to an ambassador at court. He quickly makes a hash of it, constantly conflicting with the ambassador, whom he finds pedantic. The final straw is when Werther interrupts a party meant for the aristocrats. He is asked by the host to leave, and Werther, embarrassed, resigns his position. After wandering for a bit, he returns to Wahlheim.

Werther’s mental health deteriorates after returning to the village. Charlotte and Albert have wed during Werther’s absence, and Werther is jealous of Albert. He spends increasing amounts of time at Charlotte’s house, acting possessive and jealous. Albert feels uncomfortable around Werther and advises Charlotte to cut off ties with him. As Werther spirals downward into despair and alcoholism, a man in Wahlheim murders the servant of the woman he loves in a jealous rage. Werther, seeing himself in the man, defends him and fruitlessly tries to save him from the gallows. Realizing he will never marry Charlotte, he kills himself with a pistol. The suicide goes poorly, and Werther spends hours suffering horribly. Nobody attends his funeral, and he is buried without religious rites.

Themes

The Sorrows of Young Werther caused a sensation upon publication, and catapulted Goethe to fame overnight. “Werther fever” gripped the continent; men dressed in Werther’s trademark blue coat, and the book reputedly inspired copycat suicides. Napoleon even carried the book with him when campaigning in Egypt. The reaction was not all positive; many church leaders denounced the book and it was banned in a few countries.

I find the reaction puzzling; while Goethe sympathizes with young Werther, he also portrays his flaws. Werther is self-centered, temperamental, and has no ability to take a hint. Why did young Europeans want to imitate Werther, of all people?

Feeling over Thinking

The essayist Thomas Carlyle said Werther gave expression to the “the nameless unrest and longing discontent which was then agitating every bosom.” Young Europeans were tired of the rationality of the Enlightenment and wanted to feel things again, even if it was painful. And Werther has feelings in spades. Werther is an emotional young man; when he is happy, everything is perfect, and when he is sad, it is the most crushing despair. Werther notes how strong his feelings are but considers it a sign of his genius rather than a flaw.

I have been more than once intoxicated, my passions have always bordered on extravagance: I am not ashamed to confess it; for I have learned, by my own experience, that all extraordinary men, who have accomplished great and astonishing actions, have ever been decried by the world as drunken or insane.

Despite Werther’s testament to his genius, we seldom see it. Art is supposedly his talent and profession, but he spends very little time doing it. He instead prefers to spend his time in nature or reading poetry. Nor does he learn from his mistakes; he tends to repeat them over and over again. If anything, Werther’s temperament is his undoing; it’s the reason he loses his job, and eventually causes him to commit suicide. However, in a society that often emphasized stoicism, I can see how young Europeans would like Werther: he is unafraid to take an unconventional path and act on his feelings. Albert, Werther’s polar opposite, is the exemplar of this society. In a discussion of suicide, Albert tells Werther that suicide is the coward’s way out:

It is much easier to die than to bear a life of misery with fortitude.

Werther, in contrast, defends the act:

“Human nature,” I continued, “has its limits. It is able to endure a certain degree of joy, sorrow, and pain, but becomes annihilated as soon as this measure is exceeded. The question, therefore, is, not whether a man is strong or weak, but whether he is able to endure the measure of his sufferings. The suffering may be moral or physical; and in my opinion it is just as absurd to call a man a coward who destroys himself, as to call a man a coward who dies of a malignant fever.”

Authenticity

Perhaps another reason The Sorrows of Young Werther was so popular was that Werther rebelled against the structure of society. Werther has little patience for class distinctions and is happy to converse with peasants as well as aristocrats. In a socially stratified society like 18th-century Europe, this must have been a breath of fresh air. That’s not to say Werther is a paragon of equality; he thinks himself better than both groups. He imagines peasants to have an idyllic, simple, life free from the higher-level worries that plague him. He imagines that they have no desire for freedom:

If you inquire what the people are like here, I must answer, “The same as everywhere.” The human race is but a monotonous affair. Most of them labour the greater part of their time for mere subsistence; and the scanty portion of freedom which remains to them so troubles them that they use every exertion to get rid of it. Oh, the destiny of man!

Werther treats the peasants with a mix of condescension and paternalism while living off the fruits of their labors. He cherishes the virtues of self-reliance by growing one’s own food but relies on his servants to feed him. Later, when Werther goes to work for the ambassador, he is treated by the nobility the same way he treats the lower classes. In a fit of pique, he resigns his position, a freedom the peasants he treats high-handedly do not have. Werther sees through the pretensions of the aristocrats; however, he does not see through his own.

Unrequited Love

Unrequited love is probably the theme that resonated the most with young Europeans. The love triangle in the novel is based on Goethe’s own experiences; the third leg of the triangle, Karl Wilhelm Jerusalem, committed suicide as well.

The Sorrows of Young Werther isn’t a story of star-crossed lovers held back by society; Werther and Charlotte belong to the same class, and they regularly interact in public. Even from Werther’s unreliable narration, it’s clear that Charlotte prefers Albert over Werther. Werther is warned before he even meets her that she is already engaged, and Charlotte tries to dissuade him. But Werther persists in his obsession, even though it’s not particularly clear why Werther is obsessed with Charlotte. Werther seldom describes her, saying that words cannot capture her nature. True, they have a shared bond over music and art, but Werther shares that interest with other women, such as Mrs. von B–. I think Charlotte’s appeal to Werther is that she is an unobtainable object. If he actually did marry her, he probably would not like her as much.

To Goethe, this obsession can only be destructive. Werther’s behavior gets weirder over the course of the novel, and Charlotte has to constantly tell Werther he is overstepping her boundaries. For example, Werther kisses the letters Charlotte sends him:

One thing, however, I must request: use no more writing-sand with the dear notes you send me. Today I raised your letter hastily to my lips, and it set my teeth on edge.

When he inadvertently intercepts a letter from Charlotte to Albert, he reads it and pretends that it’s addressed to him. Charlotte catches him and makes it clear that he has gone too far. Albert even advises her to cut off all ties with him, disturbed by his behavior. Charlotte, however, is reluctant to cut off all ties with him, though she does ask him to visit less frequently. Why does Charlotte maintain their friendship? Is she afraid to be rude, afraid that Werther will harm himself, or does she genuinely values his friendship. I think a companion novel from her perspective would be fascinating.

The book was a great read, and I was pleasantly surprised at how Goethe portrays his protagonist: Werther is not the tragic hero he imagines himself to be. I find the craze over the novel fascinating. Why did so many people see themselves in Werther, and look past his many flaws? What made this book resonate with so many people? The books that launch crazes these days, such as Harry Potter and Twilight tend to be much less nuanced and feature likable protagonists. Perhaps future generations will find our heroes as unlikable as I find Werther.