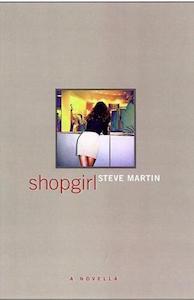

Shopgirl

“It’s pain that changes our lives.”

Shopgirl. By Steve Martin. 130 pages.

Shopgirl is a story of finding love, or if not that, at least finding yourself. The prose is sharp and frequently hilarious, but it has a vulnerability to it that makes the book stand out. Martin has a sharp eye for his characters and succeeds at conveying the bleakness of their inner lives.

Martin’s style is unique. I’ve never read another book written in the same way. It’s prose-heavy, dialogue-light, and narrated in the third person by someone who knows the characters better than the characters will ever know themselves.

Synopsis

Mirabelle Buttersfield works the ladies’ gloves counter at Neiman Marcus, the sort of thing nobody buys anymore. As a metaphor for her life, it is apt - she is lonely, unfulfilled, and depressed. Her dream is to be an artist, but the few drawings she sells are not enough to pay the bills. She goes home to two cats:

One is normal, the other is a reclusive kitten who lives under a sofa and rarely comes out. Very rarely. Once a year. This gives Mirabelle the feeling that there is a mysterious stranger living in her apartment whom she never sees but who leaves evidence of his existence by subtly moving small, round objects from room to room.

She meets slacker Jeremy at a laundromat, and they go on a series of bad dates. But Jeremy is at least there, at least interested in her, and Mirabelle sleeps with him in the vain hope that she will find companionship in a lonely world. Jeremy is not the smartest or most ambitious of men:

Jeremy’s thought process is so thin that he has the happy consequence of always ending up doing exactly what he wants to do at all times. He never complicates a desire by overthinking it, unlike Mirabelle, who spins a cocoon around an idea until it is immobile. His view of the world is one that keeps his blood pressure low, sweeping the cholesterol from his relaxed, freeway-sized arteries. Everyone knows he is going to live till age ninety, although the question that goes begging is, “for what?”

Then Mirabelle attracts the attention of Mr. Ray Porter, a fifty-year-old Seattle tech millionaire. They begin an affair, where Mirabelle falls in love but Ray doesn’t want to commit - she is too young for him. However, neither understands the other, as illustrated by this conversation:

“But I love seeing you and I want to keep seeing you.”

“I do too,” says Mirabelle. Mirabelle believes he has told her that he is bordering on falling in love with her, and Ray believes she understands that he isn’t going to be anybody’s boyfriend.

“I’m traveling too much right now,” he says. In this sentence, he serves notice that he would like to come into town, sleep with her, and leave. Mirabelle believes that he is expressing frustration at having to leave town and that he is trying to cut down on traveling.

“So what I’m saying is that we should be allowed to keep our options open, if that’s okay with you.” At this point, Ray believes he has told her that in spite of what could be about to happen tonight, they are still going to see other people. Mirabelle believes that after he cuts down on his traveling, they will see if they should get married or just go steady.

As Ray Porter continues to see other women, things come to a head, with Mirabelle asking “So are you just biding your time with me?” She eventually breaks it off with Ray. Mirabelle meets Jeremy again, who has reformed himself thanks to a road trip filled with self-help books. She leaves her job to work for an art gallery in San Francisco, where she finally realizes her dream of becoming an artist. As Mirabelle becomes more distant to Ray, he reflects on how his attempts to keep her at arm’s length doomed their relationship.

Themes

Loneliness

Each of the characters in Shopgirl is isolated and tries to deal with it in different ways. Mirabelle, whose job epitomizes her loneliness, spends her time cooking elaborate dinners for one and working at Habitat for Humanity on the weekends. Despite being in a city brimming with life, the few interactions she has with people are superficial. She wants to be loved but is too timid to go out and look for it, preferring to stay in her depressive shell. Over the course of the novella, she learns to be more outgoing, to understand what she wants, and to demand it from life.

Ray, four years divorced, looks for companionship in a series of meaningless one-night stands. To him, relationships are transactional. He tries to buy Mirabelle’s affection by paying off her student debt and gifting her a new car, but he doesn’t open up to her or commit to her. This is the root of his loneliness: he wants to keep his lovers at arm’s length so that he can have sex while looking for “the one.” What he doesn’t realize is that his desire to be closed to others is the same thing that keeps him from finding a mate.

His interest in Mirabelle comes from the part of him that still believes he can have her without obligation. He believes he can exist with her from eight to eleven and enter a private and personal world that they will create that will cease to exist in the off hours or off days. He believes that this world will be independent of other worlds he might create on another night, in another place, and he has no intention of allowing it to affect his true quest for a mate. He believes that in this affair, what is given back and forth will be exactly even, and that they will both see the benefits they are receiving.

Jeremy might be too stupid to realize he is lonely, but his slacker nature and lack of social skills isolate him from the rest of the world. However, he is the character that shows the most growth in the novella, going from an immature layabout to a successful, polished businessman. His willingness to open himself to Mirabelle and commit to her contrasts with Ray, who, by the end, is still alone.

Relationships

To assuage their loneliness, the characters of Shopgirl turn to romantic relationships. Rather than a source of connection, these relationships often become another source of pain and loneliness in their lives. Part of this is miscommunication and different expectations; often the characters hear what they want to hear rather than what is said. Ray and Mirabelle talk past each other all the time, building each other into a different idea of what they want.

Power dynamics is another issue in relationships explored in Shopgirl. The author thinks that Ray picks Mirabelle specifically because of her vulnerable qualities:

His attraction to Mirabelle is not random. He is not out and about sending gloves all over the city. His action is a very spontaneous and specific response to something in her. It may have been her stance: at twenty yards she looks off-kilter and appealing. Or maybe it was her two pinpoint eyes that made her look innocent and vulnerable. Whatever it was, it started from an extremely small place that Mr. Ray Porter never could have identified, even under torture.

Ray tries to buy her affection with expensive gifts, but he refuses to see that by withholding true connection from her how much pain he is causing her. To him, it is a transaction; they both get what they desire out of their relationship, and it is equal. But it is not equal for Mirabelle; she is not getting the companionship or love she truly desires. Ray, by withholding his affection, is the one in control. And yet, despite his aloofness, it is also clear that Ray genuinely cares about Mirabelle. When Mirabelle’s depression medication stops working, he nurses her back to health, expecting nothing in return.

In the end, though, relationships are not static things. Ray and Mirabelle manage to stay friends even after they break up, shifting to more of a parent-child relationship. The end of the novella is left ambiguous, refusing to tie up loose ends. By refusing to give a happy ending to the characters, Martin suggests that relationships are ongoing processes rather than things with a fixed end, continually evolving.

Shopgirl is a poignant meditation on the complexity of relationships and how hard it is to find connection in a disconnected world. The prose manages to be both sad and funny at the same time, defying easy classification. For such a little book, it is quite complex and intricate.